Dr James Robinson

Saturday 24.08.19 Session 2 – Dr James Robinson session on the Mangahawea Bay Excavation

Mangahawea Bay: A Site of Early Polynesian Settlement

Dr James Robinson, Regional Archaeologist, Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga

The government has employed Dr James Robinson for much of his postdoc career, and yet his work has been embedded in and informed by what is called outside New Zealand “indigenous archaeology,” research into the historic and prehistoric landscape in service of and in collaboration with the original people of the land, the tangata whenua. In Aotearoa the weaving together of technical, scientific, institutional knowledge with Maori knowledge of the country has a proper name, Mātauranga, and that word characterizes much of Robinson’s work. As Northland Regional Archaeologist for Pouhere Taonga his responsibilities include research and protection of Maori cultural landscape and artefacts. In this aspect of his work he collaborated with Department of Conservation History Ranger Andrew Blanshard in undertaking the archaeological investigation of Mangahawea Bay, led and funded by Te Rawhiti Marae’s Arakite Charitable Trust, with a combination of hapu resources and grants from Tuia 250. Robinson’s presentation and paper explain that relationship, its origin and effects, and how the resulting excavation has not only rewritten New Zealand archaeology, but has also set a new international standard for indigenous archaeology.

On behalf of Arakite Charitable Trust:

Ko Senata toku waka

Ko parihaka toku maunga

Ko Hotio toku awa

Ko Porowini toku marae

Ko Ngait Pakeha toku iwi

Ko James Robinson

The Arakite Charitable Trust reopening of the archaeological investigation at Mangahawea Bay began in 2017 under the tikanga and mana of Matutaera Te Nana Clendon, one of the Trust’s three trustees along with Robert Willoughby and Professor Manuka Henare. Clendon comes from Te Rawhiti and claims Rakau Mangamanga as his Maunga, that traditionally is remembered as a waypoint for Polynesian explorers and settlers coming to this southern corner of the Polynesian Triangle. His interest in navigation and voyaging, and his intimate knowledge of his original home, which is Moturua Island, inspired a reopening of an early Polynesian settlement site partially excavated back in 1981. Though his perspective is based in hapu connections his view and interests spanned wider Maori connections through space and time to a particular Pacific connection with Mangahawea Bay. Matua Clendon engaged with Andrew Blanshard from the Department of Conservation, and myself from Heritage New Zealand, and both Government agencies joined his program, because this networking of knowledge is how archaeology is supposed to work.

Hei tangata, hei tangata, hei tangata…….

My esteemed colleague Prof Richard Walter of the University of Otago – who was, weirdly, my contemporary at the University of Auckland, and then 20 years later supervised my PhD – has described a Pacific background to our problem, and has explained what was going on at the time of voyaging when the islands within Aotearoa’s Hawaiiki had the same material culture, reflecting how they were culturally bound together, and so provide the resources both human and material that were required for successful exploration and colonisation of Hawaii, Rapanui and finally Aotearoa. Only when there were no more empty lands left to be colonised did this cultural binding start to break apart – again reflected in change and divergence in the material culture of individual island groups within Hawaiiki.

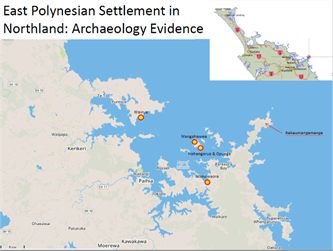

So, our particular work began at Mangahawea Bay, a site of early Polynesian settlement from Eastern Polynesia Hawaiiki, a place where those colonising waka finally landed and started the process of becoming distinctly Maori. Now Prof Walter and others like Prof Simon Holdaway of Auckland University have been working on different islands and places around Aotearoa and they both see related developments on this island located in Northland in New Zealand’s Bay of Islands. Moturua Island itself is the focal point that pulls together korero history regarding both the traditional knowledge of Moturua’s history and its archaeology, as well as related purely technical sciences. Combined, these sciences and the inherited wisdom of this island tell interesting stories.

The Polynesian exploration and settlement of the Pacific ended when they reached the human inhabited New World of North and South America. When Walter tells how society changed back in Hawaiiki – the Maori homeland – after the 1400s when there were no longer empty places to be colonised, then a similar cultural change occurred within the colonists who settled Aotearoa. We see this change within broad perspective because at the moment the tupuna (ancestors) first stepped ashore they were East Polynesian. Yet at that moment they began a new hikoi (voyage) in Aotearoa to become distinctly and uniquely Maori. That voyage continues to this day.

So, when we look at early archaeological sites around Aotearoa, they are strongly Polynesian in design. After the land and the people interact in interesting ways, the later archaeological sites have changed to become recognisably Maori. So, what sort of early sites would we find, when people first came to Aotearoa?,

Aotearoa New Zealand can be seen as the last ‘bus stop’ so to speak in the human settlement of the World. Within science’s widest view and widest grasp, archaeology talks about connections from the point of the very earliest understanding of humanity, to embrace and explain our common humanity as out of Africa we walked, then around the world for all our complex human reasons. Where humanity was temporarily stopped by permanent water we see time gaps in settlement. Settlement from island South-East Asia to Australia-Papua-New-Guinea was delayed until 60-80000 years ago; settlement of the New World of North and South America probably 30000 years ago. The Pacific was the last place to be settled 3000 years ago because the water gaps were so large, and the islands are so small that on the scale of looking at the whole globe you cannot even see them.

Murphy Shortland’s 1995 map records the collective knowledge of traditional Maori place names in the Eastern Bay of Islands. Based on the korero of his own hapu, Matuteara Clendon focused our attention on the island of Moturua and on Motuarohia Island, where Cook anchored in his first visit to Aotearoa in December 1769.

Shortland’s map points out ‘Hikurangi,’ an ancient name Ross Ramsey finds used forty times around New Zealand. ‘Motu Rangiatea’, the name given to the small motu sheltering Manghawea Bay, is also a name found back in the Pacific. Specifically Rangiatea connects as the old name of Raiatea Island in the Society Group, a locale in Rarotonga, and a name repeated in Hawaii and in other parts of the Pacific. Rangiatea like Hikurangi is an ancestral name, and it is carried around the Pacific by related settlers.

The Bay of Islands has many hundreds of archaeological sites. The Bay has always been a popular place to live, with pockets of good soil and great fisheries, and sheltered waters for transport by waka. This range of resources and of living options made the Bay of Islands habitable, and desirable, from the times of first settlement, through the classic period, and on to the modern day. The early sites are distinguished most easily from later Maori sites by the remains of moa and seal. Prof. Ian Smith showed that seals were eliminated from areas of habitation very early in the settlement period. Moa similarly became extinct rapidly after human arrival. This is because they had no predators, did not breed every year, and their physiology suggests such a slow gait that people could easily hunt them. Cooked moa and seal bone in a haangi excavated at Mangahawea Bay suggests to the archaeologists that this is a very early settlement site.

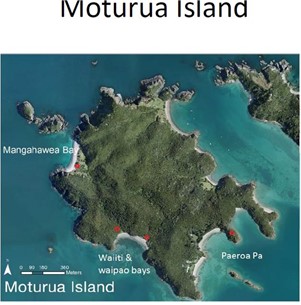

Moturua Island.

Mangahawea Bay lies at the northwest corner of the island. The dot near the south end of the beach marks a midden first recorded by Dr Phil Moore in 1980. Moore noted the midden had an underlying area of bone, particularly noting that it contained a shell – Cellana denticullata – the Cook Strait limpet. This limpet’s primary distribution is 900km south in the Cook Strait but formerly its distribution extended into the Bay of Islands. Its importance is that it became extinct in the Bay of Islands soon after human arrival. Like moa and seal: in a cooking deposit in the North, the presence of the Cook Strait limpet means the site is early. So this finding is among researchers’ first signs that Moturua Island’s archaeological record might extend all the way though the human history of Aotearoa.

Half a millennium after the Polynesian ancestors of Maori first settled the island, Moturua’s southside bays of Waiiti and Waipau served as watering places for the early European visitors. When Lt James Cook, Joseph Banks and the Navigator Priest Tupaia arrived from the society Islands in 1769 they went to Waipau for water. The French explorer Marc-Joseph Marion Du Fresne found the same bay, and fresh water, three years later. He also set up a camp, a hospital and a forge in the adjacent Waiiti Bay. After the death of Marion Du Fresne his men marched from Waiiti Bay to Paeroa Pa and attacked the pa. Note that this is the only attack with firearms on a traditional pa designed for hand held weapon fighting, that was recorded in the explorers’ journals. Korero (stories) about this same event is recorded by the Maori, in their whakapapa.

Out of all this rich heritage environment, Mangahawea Bay is in some way the most obscure, and yet most worthy of attention. How did we get there? How did we learn of its value?

In 1981, before the Department of Conservation was founded in 1987, the Bay of Islands Maritime and Historic Park was set up to manage Crown land in the Bay under the Lands and Survey Department. One of the archaeologists who worked for that department was Jan McKay. She noticed Phil Moore’s site record, concerning a large midden, and, fearing coastal erosion would destroy the site, McKay went to carry out an archaeological investigation.

The slide “McKay Moturua Excavation” shows young archaeologists: On the left rear is Richard Shepherd at the time a lecturer at Auckland University. David Veart and Mike Taylor (back row third and fourth from the left were archaeology students while John Coster (back right) was an archaeologist working for the Lands and Survey Department in Auckland. These young scientists dug along a section of stream bank, comprising three excavation units and one exposed stream bank section. They found material artefacts, consistent with those expected in an early settlement, including bone tabs and the resulting bone fish hooks. Associated with these early type artefacts was a large Cooks Strait limpet, Celana denticulata, no longer found in these waters. Along with normal early material culture, and a limpet that disappeared from the North early in human occupation, they found a strange pendant, not typical of classic Maori artefacts, but perhaps consistent with a Polynesian origin.

McKay Moturua Excavation

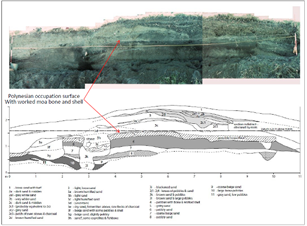

Stream Bank Cross-section.

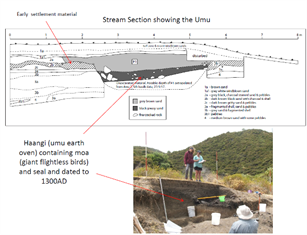

The image “Stream Bank Cross-section” shows the section of the stream bank diagrammed after the 1981 excavation. Red arrows point out the zone of Polynesian occupation, where was found worked moa bone and shell. There is a particular cut visible in the strata, at point 4 on the diagram. Matu Clendon, who grew up on this island, explained that this may have been a small pit for the storage of kumara: digging the pit near the side of a dune or dry streambed allows easier and more complete removal of stored kumara by simply pushing away the sand from the side of the pit, and letting the tubers fall out. As a child, Clendon had witnessed the use of this technique. Of course the stratigraphy shows that the cut is a later intrusion into the early deposits, but this korero shows how we can use traditional knowledge to interpret stratigraphy through ethnographic analogy, and illustrates how composite archaeological science – incorporating traditional evidence – works to explain culture.

After several attempts to write up the excavation, Director Jan McKay passed away in 2017, without completing any report. The collection of material culture had reverted to Moturua’s land manager, the Department of Conservation. Andrew Blanshard – then History Ranger for the Bay of Islands – reviewed the small artefact collection with marine biologist John Booth and with rangatira Matu Clendon. From different perspectives Booth and Clendon agreed that this small trove of evidence pointed in important directions.

Mangahawea reopened.

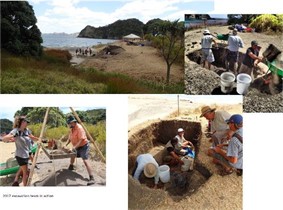

So in 2017, under iwi management and Clendon’s tikanga, archaeologists returned to Mangahawea to relocate the original excavation units. Area 1 (1981 Unit 25-26) was re-excavated under the direction of John Coster, who dug this square first in 1981. Of the original 1981 team, Mike Taylor and Dave Veart also returned to dig in 2017. And so the 2017 team, incorporating elements of the 1981 team, succeeded in its ambitious aims: relocating the 1981 excavation units, and completing the excavation of the partially excavated unit now designated Unit 1.

Excavation Overview

The red arrowed line projected on the 1981 photo embedded in the image “Excavation Overview” marks the plane of the 2017 stream section drawing (top image). Note that by 2017 erosion had claimed about a meter of the 1981 stream bank shown by the red dashed line (bottom image). The images show a dark layer marking the early horizon, the dense carbon indicating cooking. In this case it led us to a large stone-lined haangi.

2018 Excavators

Haangi Cross-section

In the image labelled “Haangi Cross-section” the section drawing shows how the cultural horizon is a visible level layer. Through this earliest cultural horizon, the haangi cuts down through the sterile pre-settlement soil, like the previously referenced kumara pit. The haangi pit was lined with large stones and contained a small amount of moa and seal bone. This is quite different from the material culture Richard Walter found at Wairau Bar at the top of the South Island where haangi were full of moa bone, thrown back in after the meal. Here there is cooked moa bone distributed in the site, but not specifically discarded in the haangi. The Wairau Bar haangi dates from the same era, but the Mangahawea haangi is not used in the same way. Still, they are about the same size at 5m long, large for a haangi and stone lined. Stone linings are an example of cultural continuity because they persist in haangi pits to this day when they are dug in sandy soil.

Because of these findings in material culture, and because of Clendon’s inherited korero, in 2018 we had new questions. If early, Mangahawea should be a nucleated site, if it still followed the model of settlement found back in Hawaiiki: So where was the village? We think we found where the dogs were kept together. We think we have found the haangi and the general cooking zone, but we could not see the village. Had it already become the modern Maori village, with dispersed activity areas? We were not sure.

So when the Tuia 250 calls for funding proposals were published, we considered how to return to Mangahawea,. The Arakite Charitable Trust – established by Matu Clendon, Robert Willoughby and Prof Manuka Henare – applied for Tuia 250 funding, with support from the Department of Conservation, Heritage New Zealand, and the University of Otago. It is worthy of historical note to explain that the application was made, and funding received, by Arakite Charitable Trust, which represents Ngati Kuta and Patu Keha. These comprise the houo kainga, the hapu of Rawhiti, the tangata whenua and possessors of the land, and of its korero. Outside academic and government agencies stood in support, but the money and the management were in the hands of the Trust.

With Arakite Trust guidance and funding, we returned to the site in January 2019. Other aspects of kotahitanga and whakamōhio include the carving of a pou reconnecting Maori as a group to their Pacific tupuna – celebrating the scientific investigation of traditional wisdom and sharing with the wider Pacific community. In terms of tikanga this can only happen because Clendon traces his descent through Ngaere Raumati and through Nga Puhi.

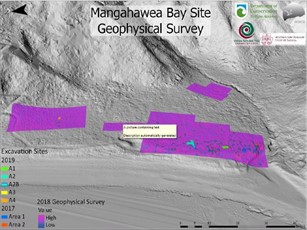

In addition to the overarching cultural importance of the dig, there was good science. Geophysical study included magnetometry to locate subsurface structure, and a LIDAR survey yielding a 20cm contour.

LIDAR combined with geophysical survey.

When LIDAR is combined with the geophysical survey, patterns – anomalies – concentrate at the south end of the bay near the beach, which is the north side of stream, circled at the lower right corner of the image. The 1981 and 2019 excavators worked here. To complete the picture, we worked back inland from beach and stream. That few anomalies show in the geophysical imaging do not indicate a lack of archaeology, only that there was nothing for magnetometry to see. And so we designated areas 1, 2, 3 and 4: two inside and two outside the original investigation zone as the focus of this season of investigation.

Nearest the mouth of the stream and including the areas of earlier excavation, areas 1 and 2 yielded haangi and other settled activity areas. Outside that area, and more inland, areas 3 and 4 and the environs exhibited layered, often much disturbed evidence of early historic Maori horticulture of European-introduced white potatoes and hints that we may have a relic area of taro cultivation, possibly relating to the initial phase of excavation.

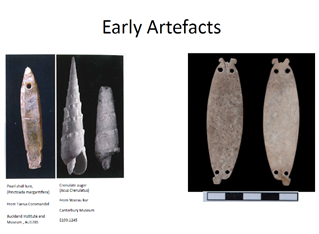

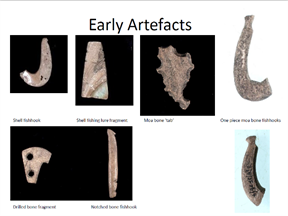

The left image in “Early Artefacts” shows shell artefacts found in New Zealand. The left image shows the pearl shell fishing lure from Tairoa and the crenelated auger from Wairau Bar. Both of these are shell species not native to New Zealand and so appear to have been brought here by early settlers from the Pacific. At the right are the two sides of the pendant lure excavated at Mangahawea Bay in 1981. Dr Kat Szabó calls this a ‘pa kahawai’ fishing lure, a flasher attached to a wooden fish hook. The artefact had gone through several incarnations. Three drilled lugs are visible and a fourth was admitted by archaeologist Mike Taylor to have been knocked off during the 1981 excavation. While the lugs, in shell material, would have been strong enough for attachment to the hook, the immediately adjacent holes weaken the structure. And so the working hypothesis is that this fishing lure then ended its life as a decorative pendant.

Such an old, fragile and small bit of shell is hard to identify and harder to name as an object. Szabó and the team’s marine ecologist John Booth, both experts, identify the shell as paua species. Szarbo argues for the silver paua while Booth believes it to be the black-lipped paua. Experimental archaeology by Kemp suggests that only the larger black lipped paua would match the gentle double curvature of the excavated artefact. Since both species of paua are only native to New Zealand the artefact must have been made here, however the design is Polynesian. Research to date suggests that nothing matches this artefact in New Zealand collections, and in the historic contact period with Maori they do not seem to have used these lures. So if the identification as a pa kahawai is accurate, then it is a Polynesian design executed by earliest inhabitants, in local shell.

This is a working hypothesis, a process of work, and the point is to test and check, and we are using traditional knowledge as part of that process. While we are drawing a long bow here, the working hypothesis relies on a combination of technical information and experimental analysis set in context with traditional knowledge. This synthesis of mātauranga in its several senses – particularly mātauranga pūtaiao illuminated by mātauranga Māori – has guided our methodology at Mangahawea.

“Mangahawea fish hook manufacture” shows the range of artefacts excavated from Mangahawea Bay. Fish hooks and scrap from their manufacture, which we call tabs, characterize the whole deposit. Most objects recovered in site archaeology have been discarded, and so most are broken. On the left are shell, and the right are bone, probably sourced from seal or moa. The shape of these hooks is found in the Hawaiiki homeland, as Richard Walter’s work shows.

Bottom left and top right are tabs. The pattern of a bone fish hook is scribed out of a flat bone – a scapula – and then the hard material is drilled around the scribed line, in hopes the hook pops out when finished. The drilled scrap is left. Its presence in numbers suggests a place of manufacture.

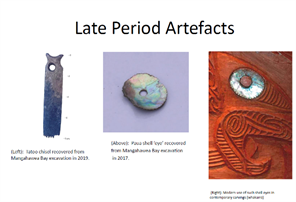

The wider range of the 2019 dig – away from the proved archaic site at the stream mouth – produced later artefacts. Those we could not date, because of the disturbance by agriculture of the rest of the surface. Left, in the image labelled “Late Period Artefacts” is a tattoo chisel, which might be early or late. Joseph Banks records their use on Moturua (or Motu Arohia) in 1769 and notes that they were identical to those he had observed the previous month in Polynesia. Between the archaic (early) period of Polynesian settlement and the later historic arrival of Europeans, the Maori also developed a new and unique to Aotearoa style of tattooing, carving the skin of the face to produce the tā moko. The use of both types of chisels persisted into early colonial times.

John Booth also identified the paua shell in the image, which is clearly the eye of a pou figure, such as we see today in Maori whakairo carving. This was found at the stream mouth, but in disturbed dune deposit, and so cannot be dated by stratigraphy or association.

These small food storage pits, such as the one labelled, were excavated in 2019. They are another feature typical of Maori horticulture. Unlike the artefacts discussed above, disturbed from original deposition, these pits give us dating and mapping points. They can be located by lab work in time, and by traditional knowledge in use, and in the story of the site.

New discoveries outside the previously investigated archaic deposits in Area 1 include the identification of soils modified with shell and fish bone and pebbles in the upper stratigraphy. These cover nearly the whole of the level land at Mangahawea and are believed to relate to the provisioning trade with the whaling fleets that came to the Bay in the 1820s

These historic Maori gardens overlie a buried stream. Found in Area 3 and shown in the image “Gardens – early taro?” the streambed likely was buried later in the sequence to make the historic gardens. The small sticks in the image mark little pockets of charcoal. This garden patch in the edge of a shallow streambed might be something very important: a much older taro garden that underlies and therefore predates the potato garden. According to traditional whakatupu this spacing of the plants is the old way to grow taro. Orange colour is due to the high water content on what was once the side of the stream. Taro likes wet feet but kumara does not. Samples are out currently away being analysed.

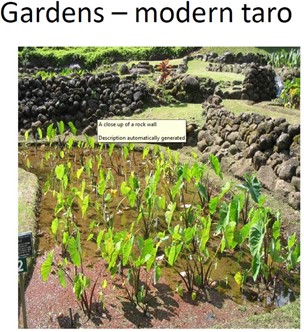

The pattern of planting in “Gardens – modern taro”, resembling the depressions in the buried streambed at Mangahawea, shows modern taro gardening at Puna Keia region of Mangaia, in the Cook Islands.

Taro is one of the early crops brought from Polynesia, and managed in horticulture and in diet as the settlers made themselves the Maori. Still grown in the North, taro is one of these early taonga, before kumara became the dominant crop in Aotearoa. Visiting the island of Mangaia in the Southern Cooks, with Professor Richard Walter, we were told by the inhabitants that kumara was pig food: humans did not eat it, rather they ate taro.

There is a tale that in recent years Mangaian taro – a delicacy in the Cooks – would arrive in Auckland, and the Cook Islanders would descend on the shipment and take the best. Then the remainder went to Wellington where the Cook islanders based there picked over the rest. The culls then went to Dunedin, where those Cook Islanders wondered what had gone wrong with Mangaia taro?

Conclusions

So what did we find, and what do the material remains mean?

– Worked tools indicate it is more than just a temporary fishing camp. How much more we don’t know.

– Geophysical analysis identifies occupation along the beach frontage, although the nucleated village expected of a Polynesian modelled settlement has not been found, if there was one.

– Features such as the large stone-lined haangi, with cooked moa bone, indicate early occupation.

– Gardening is found throughout the sequence with some appearing to relate to early Polynesian-style taro production, overlaid by later extensive historic white potato gardens which covers the whole arable Bay. During the Musket Wars white potatoes bought muskets, which were essential for survival. The small islet called Motu Oi, next to Motu Rangiatea, that sheltered Mangahawea Bay, was the site of the last battle between Ngare Raumati and Ngapuhi. So this place has been in Ngapuhi occupation until 1898.

While a few more excavated objects await laboratory analysis, we have not found any proven heirlooms, artefacts that crossed the Pacific on a waka, such as Tairoa’s pearl shell lure or the Wairau Bar crenulated auger. But the pa kahawai made from New Zealand paua appears stylistically unique. Later pa kahawai flasher lures are radically different, so we judge this one to be early. How early: not sure but this type of lure adapts early, and therefore could be from the first 20 years of settlement, but definitely within the first 100 years as it was excavated from the deepest and therefore earliest cultural layers. This artefact perhaps starts to tell the story of how the first Polynesian settlers began the long phase of adaptation to become Maori. The analysis of Mangahawea and its place in archaeology, especially in prehistory, is a work in progress.

What is important about Mangahawea Bay?

Culturally, its archaic aspect is that of an unusually early Polynesian settlement, which appears to reflect an early phase of cultural adaptation from an East Polynesian settlement to a distinctly Maori one.

From a technical standpoint, Mangahawea exhibits a rare, intact stratigraphic record. Dated stratigraphy extends from 1300AD – as early as anywhere in the country – into the historic period. Historic artefacts such as gun flints and bottles show this continuity of occupation. In other parts of the world finding site stratigraphy spanning early to late is common. However, the Maori way of living across the landscape, removing and repurposing for the season or for change in group population or structure, for war or for its avoidance, or for food-gathering, results in archaeologists struggling to find continuous stratigraphy. So, aside from its cultural and historical significance, Mangahawea is important to archaeologists because of intact stratigraphy. In this particular sense of continuity Mangahawea is the key site for the Bay of Islands.

From the standpoint of cultural study, and its refinement by integration in depth with the living knowledge of the culture being studied, the development of the Mangahawea site is of the greatest importance, perhaps revolutionary. Indigenous archaeology is the term for sites and interpretation developed in cooperation with the people being studied, or with their descendants. Because of the finance and logistics, official regulation and professional discipline, the “indigenous” component of most archaeological research is usually integrated into compartments of the process judged relevant to indigenous expertise: traditional location, traditional permissions of practice, traditional interpretation, and continuing evidence and knowledge: Think about how thin our knowledge of waka would be if we only had excavated boats, without korero, without mātauranga Māori.

The development of the Mangahawea site excavation was revolutionary, from concept to execution, even to publication, because every step of the way has been conceived, located, mapped, planned, organized, moved, dug, blessed, catalogued, presented and now published, with tribal knowledge, tribal concept, tribal ritual, tribal money and tribal hands-on management. We cannot say Mangahawea is the only example in the world of this complete integration of management of archaeology, by the people being studied, but it is the only one our researchers have been able to find. This management system included Maori tikanga. Even without the cultural, historical and technical achievements of this excavation, its coherent conception and management under the mana of Matutaera Te Nana Clendon, ONZM, as well as the organizational aegis and grant management of Arakite Charitable Trust, have made the Mangahawea excavation worthy of international note.

WHĀKINGA

I must thank . . .

The Mangahawea excavation was completed in compliance with Maori tikanga. Under the tikanga and mana of Matutaera Clendon, while observing protocols developed by Kipa Munro and Andrew Blanshard, our excavation team worked with sensitivity to the land, to the ancestors, and to the living tradition of the Maori of the Bay of Islands. Workers included fifteen academic archaeologists from the universities of Otago and Auckland, the chair of the NZAA, and six independent contracting archaeologists, and a handful of international anthropology professors, visiting for the purpose. These professionals combined in learning and in teaching a combined master class in modern archaeology, and in our revolutionary exploration of anthropology managed by the people being studied. Local Maori who arrived to watch, or to help with camp, under this tikanga, they were integrated into the archaeological team. Most were trained in the essential and laborious practice of screening soil for artefacts. Having a dedicated screening team meant faster work with a higher probability of finding relevant materials, which in turn meant digging went faster. So more digging got done. Some iwi members volunteered to dig, and along with tikanga master Kipa Munro, who was also field trained in practical archaeology, the local Maori contingent added to the volume of work, to our knowledge, and to the atmosphere of cooperative learning.

Because this expansion of learning and understanding, and what was said to be an unmatched tikanga, five professional excavators, scheduled to be away from their normal jobs for only the first week of the dig, either lied to their bosses, or quit, or blackmailed their bosses so that they could stay for the second week. Our visiting professor from Germany said that in 30 years of running his own field crews and helping colleagues, he had never felt such a sense of camaraderie, of unity of purpose, of an absence of competitiveness.

More telling, the real veterans of the site – archaeologists John Coster, Mike Taylor and Dave Veart, who worked on the original excavation 37 years earlier – agreed that the observation of tikanga protocols allowed them to end properly what they had begun in 1981. Back in those days archaeology was mainly a pakeha enterprise, and tikanga was a matter for ethnologists. We were all touched to see how the veterans offered up everything that they could. John Coster arguably one of the country’s most experienced archaeologists, regarding sheer number of surveys and excavations, said that the wairua (spirit) of the dig was first class.

I would like to acknowledge all the academic and professional and iwi participants, but the inclusive nature of the way the dig progressed makes it impossible to name everyone, so I will leave it at this: Tena koutou, tena koutou, tena koutou.