Ockie Simmonds

Saturday 24.08.19 Session 5 – Ockie Simmonds session on “Coming of Maori”

The Coming of the Māori – Identifying a Specific Arrival Date of the Māori to Aotearoa-New Zealand

Ockie Simmonds[1] and Kiyotaka Tanikawa[2]

Ockie Simmonds, of the Society of Māori Astronomy Research and Traditions, has travelled the extensively in search of knowledge regarding Maramataka (the Māori lunar calendar). In Hefei, China, he heard a paper by Kiyotaka Tanikawa, of the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan, who is a specialist in archaeo-astronomy: tracking the heavenly bodies back through time. Tanikawa’s work allows him to date with some certainty traditional history and even oral legend related to astronomical events (think of Halley’s Comet and the Norman invasion of England). The art and science of Maramataka already had Simmonds thinking along this line. And so he initiated this international research collaboration, intending to coordinate Maramataka dates with the international Gregorian calendar. The compelling argument of this paper – combining whakapapa with archaeo-astronomy in a masterful display of the use of mātauranga – is the result.

Abstract.

A hundred years ago Western historians determined that a ‘Great-fleet’ carrying the Polynesian people arrived in New Zealand the year 1350 AD. The arrival date was derived using whakapapa or genealogies which served as an elementary chronology to fix an arrival date. The arrival date of 1350 is entrenched in New Zealand’s national consciousness and remains largely unchallenged. This research proposes that the celebrated ‘Great-Fleet’ arrived in New Zealand on December 1408 AD. This new arrival date is derived by a closer analytical interpretation of the whakapapa, or genealogical evidence relating to members of two specific sailing vessels the Tainui and Te Arawa vessels that were part of the “Great Fleet” arrival. This revised genealogical analysis underpins the arrival-period with other critical supporting key information. Importantly, the new proposed arrival period is reinforced by archaeo-astronomical evidence indicating that a full solar eclipse occurred in October 1409 AD. Traditional narratives advocate the historic solar eclipse event was witnessed by prominent members of the Te Arawa vessel after their arrival in New Zealand. The key to deriving a specific Gregorian date of arrival is that Māori retained the dates of departure and arrival within their traditional oral histories and their luni-solar calendar system, the maramataka. Furthermore, from the solar eclipse event in 1409 and further genealogical analysis and other environmental supporting evidence we propose the voyagers arrived in New Zealand the previous summer of 1408.

Keywords: Luni-solar calendar, Archaeo-astronomy, Māori.

Introduction

The Settlement of Polynesia

The descendants of their Austronesian ancestors, the proto-Polynesians, set off from the Asiatic mainland at least 6,000 years ago (M. King, 2003:31; J. Evans, 1998:15). They left the Asiatic mainland shores to follow their stars and environmental signs, and sailed into the rising sun right across the Pacific Ocean to become the most extraordinary navigators in history. The proto-Polynesians island-hopped across the Western Pacific through Micronesia (P.H Buck, 1938:45, D. Lewis, 1977:13, M.P.K. Sorrenson, 1979 [1983]:12). In settling the wide expanses of the Pacific Ocean, the Polynesians used unique astronomical star, environmental and seasonal navigating skills that allowed Polynesians to discover and colonise every habitable island in the Polynesian triangle (M. Lee, 2018:18; P.H. Buck, 1938:60).

The Arrival of the “Great Fleet”

The Māori ancestors, with their extraordinary navigational skills, set off from their homes in Eastern Polynesia for a new homeland in New Zealand, the last major land mass on Earth to be systematically colonised and settled (P.H. Buck, 1938:259; J. Evans, 1998:21). The mass migration and settlement of Aotearoa-New Zealand from Eastern Polynesia commenced in earnest about the late thirteenth century right into the fifteenth century (M. King, 2003:50). There is no archaeological evidence of human impact at all in New Zealand before the 13th century (M. King, 2003:48).

The “Great Fleet” arrived in the estimated iconic year of 1350 AD. The early Māori voyagers with their wives, children, grandchildren, extended families, animals, plants, their gods, courage and sheer determination willingly sailed on a planned search and to settle a new homeland. There is archaeological evidence of small groups of migrants from Eastern Polynesian had already just settled, prior to the “Great Fleet”, in New Zealand. These groups all left from a wider group of islands principally of the Marquesas, Tuamotu and Society Islands in the Eastern Polynesian region. This variation in island-origins are reflected in different traditions, social orders, different tribes, and different dialects in New Zealand (J.B. Condliffe, 1971:171, 290; P. Buck, 1938:273).

The reason for leaving their Pacific homeland is still disputed. There are strong traditional narratives that food shortages, wars, political and religious persecution caused small groups to leave. What caused a mass migration and “Great Fleet” may be the result of many factors including significant environmental impacts due to changing climatic conditions leading towards the Little Ice Age (H.A Bridgman, 1983). This suggested environmental and climate-factor needs to be considered in another in-depth research paper.

Historic solar eclipse retained in traditional narratives

The dating of historical events in cultures with no written record relies on oral narratives and traditions to estimate the time of an event. The Polynesians had such a culture with no written language and no written historical records. For Māori, the dating of historical events relied on oral tradition and whakapapa. In this paper we utilise whakapapa (genealogies) in conjunction with traditional narratives, legends and stories to estimate the arrival period of the “Great Fleet”. Here however we introduce to this estimation the use of a known archaeo-astronomical event in the form of a solar eclipse to reinforce an estimated arrival period.

The full solar eclipse that is known to have occurred around the estimated time of arrival of the “Great Fleet”. According to traditional Māori narratives the eclipse experience was witnessed and the impact are still embedded in Māori legends and traditional stories. The impact of the historic arrival and the subsequent witnessing of the solar eclipse event still resonates with Māori and New Zealand’s society today. The correlation of such evidence in particular with astronomical data has never been done in relation to Māori history. This paper will describe the eclipse event, provide supporting narratives and an analysis of whakapapa and genealogy. The contents of the paper are as follows:

Part 1: Introduction;

Part 2: Legends to eclipses;

Part 3: Genealogical evidence;

Part 4: Identifying a Gregorian arrival date;

Part 5: Complementary narrative;

Part 6: Discussion and conclusion;

Part 7: Acknowledgements.

Legends to Eclipses

Eclipses in Memory

Traditionally most eclipse events are lost to history, forgotten or are not recorded in any recognisable and clearly understood form. This is certainly the situation for illiterate cultures that had not developed a written language. The question then arises about how eclipse events are remembered in regions where no astronomers, or literate scribes, are present in the region, at the time of a historical eclipse event.

Research from Tanikawa and Sōma of the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan (NAOJ) in 2010 proposed that solar eclipses are remembered in regions with no astronomers, and no literate culture when key events occur (Tanikawa and Sōma 2010). Tanikawa and Sōma proposed that if the following conditions are met, an eclipse event may be recorded, such as:

i. a solar eclipse is either total, annular, or very deep;

ii. an important historical co-occurring event takes place;

iii. a record of the event is retained; and

iv. historical oral narratives are retained through traditional legends, stories, chants and songs.

The Japanese Legend

In March 2014, the co-author for this research, Tanikawa presented a paper, ‘Delta T Variations from 1133 to 1267 AD’, at the Eighth International Conference on Oriental Astronomy (ICOA-8) in Hefei, China[3]. The presentation highlighted a Japanese historical legend. This legendary event has been proposed as recording the experience of their ancient people of witnessing a full solar eclipse. Deciding on which candidate eclipse event that it was involved gathering other historical information to narrow down which eclipse event was most likely. Some of the supporting information included identifying the reign of a Japanese emperor that was associated with the event’s time-frame. Tanikawa and Sōma of NAOJ estimated the eclipse occurred on July 13, 158 AD. Furthermore, they noted that this Japanese legend and eclipse event related to a similar legend in Korea and linked to the same eclipse at that time (Tanikawa and Sōma, 2010).

- The Arrival Narrative and Legend

The Japanese story draws striking resemblance to a well-known traditional Māori legend called Hatupatu and the witch, Kurangaituku. The similarity with the Japanese legend strongly suggests that the Hatupatu legend might also represent a full solar eclipse that can be dated. Moreover, other traditional stories complement the Hatupatu legend in time and location that represent the same historical solar eclipse event. To provide a historical context we briefly describe the arrival of two of the vessels of the “Great Fleet” and how two different groups travelled across the central volcanic region of the North Island of New Zealand. Their journey, encounters and observations are still known today and can be used to corroborate other events of the time.

The traditional narrative implies that Tainui and Te Arawa sailing vessels arrived in New Zealand on the East Coast. The Te Arawa people settled at Maketū in the Bay of Plenty. Later a group under the leadership of crew members Tia and his brother, Hatupatu, travelled inland to explore the central volcanic plateau including Lake Taupō (J. Grace, 1959[1970]: 59). Another group under spiritual leader and navigator of Te Arawa, Ngātoroirangi also set out to explore the central volcanic plateau[4]. While in these general areas of Lake Taupō the parties were overtaken by a deep totality of a solar eclipse.

This research suggests that Hatupatu had left Tia’s group earlier and headed back to their original arrival settlement at Maketū via the location of Atiamuri. At this point Hatupatu was overtaken by the solar eclipse and apparently took shelter in the rock now known and still revered as Te Kōwhatu ō Hatupatu, the Rock of Hatupatu. The legend is called Hatupatu and the bird-lady (witch) called Kurangaituku[5]. The legend tells of flames emanating from the witch’s fingers which draws a suggestion that Hatupatu may have witnessed the brilliant diamond coronal effect and therefore may have seen the solar eclipse event just before totality[6].

On the journey place names were given at different geographical locations that emanated from the travels of Hatupatu, Tia and Ngātoroirangi and are embedded in New Zealand’s society today. The naming of these geographical locations strongly suggests an eclipse event occurred at the time. The names are:

- Lake Taupō: Known traditionally as Taupō-nui-ā-Tia, meaning ‘a great darkness settled over Tia’. We suggest that the lake is named by Tia after witnessing the eclipse event.

- Rangipō: Meaning, ‘darkening sky, or dark sky’. Rangipō was named by Ngātoroirangi. Rangipō is a geographical plateau region South of Lake Taupō in the central volcanic region.

- Witnessing an eclipse event

The three intrepid explorers from the Te Arawa vessel and their respective parties were within the scope of a full solar eclipse on that momentous day and witnessed the event (see next section for details). We propose that the groups witnessed this eclipse event and embedded their observations and experience into place-names and legends. As described in Section 2.1, Tanikawa and Sōma proposed that solar eclipses are remembered in regions with no astronomers and no literate culture when key events occur if certain conditions are met. We endorse the proposals that the legend of Hatupatu is retained in the oral history of Māori has a number of key factors pointing to an eclipse event similarly to the legend that was described by Tanikawa et al (2010). Therefore, within this criteria, the legend of Hatupatu:

- Meets the criteria of traditional authenticity;

- The Hatupatu site is a recognised national geographical landmark;

- Research indicates a full solar eclipse passed over the landmark in 1409;

- Other simultaneous legends at Lake Taupō and Rangipō complement the Hatupatu legend in time and location;

- The legendary bird-women had flames projecting from her fingers, suggests the coronal effects of a solar eclipse.

- Genealogical Evidence

- Tainui and Te Arawa Genealogies

From this next section we investigate possible eclipses occurring at that time that will corroborate with the stories of Tia, Ngātoroirangi and the legend of Hatupatu. To ensure we have the correct time period we present an analysis of a set of genealogical charts that are correlated to propose a strong estimate for the arrival of Māori and the “Great Fleet” to New Zealand.

We here take a first look at the vessels Tainui and the Te Arawa that both departed together from their island homeland in ‘Hawaiki’ (Tahiti) in the Eastern Pacific. The names of the men and most women on board and their genealogies have been retained in memory by traditions, stories, waiata (songs) and recorded in literature when the Europeans arrived in the 19th Century (Stafford, 1967:19:49; Harris et al 2013, Simmons 1976:11)).

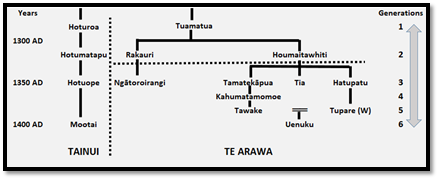

There were four generations on both vessels when they both arrived in New Zealand. The following genealogy/whakapapa (see Figure 2) is chronologically set around the crudely estimated time of arrival in New Zealand of 1350 AD (W.E Gudgeon, 1894:47)[7]. These genealogies are given as an example to show the relationships to the already mentioned Tia, Hatupatu and Ngatoroirangi from the Te Arawa vessel.

Fig. 1. The two genealogies outline the relationship of personnel on both vessels. The names from Hoturoa and below arrived on the Tainui waka. The names below Rakauri and Houmaitawhiti all arrived in New Zealand on Te Arawa.

According to the historical narrative five generations were living at the time of departure to New Zealand. The journey was estimated to take around 26-30 days (M. Winiata, 1950: 5; P.T Jones, 1995:52)[8]. Figure 1 outlines key personnel and their genealogical relationships.

The Te Arawa genealogy are as follows:

- Te Arawa personnel are: Tamatekapua (Captain), Ngātoroirangi (Priest/navigator), Tia, Hatupatu, Kahumatamomoe, Tawake (Tawakemoetāhanga), Tupare (Tūparewhaitaita – w) and Uenuku (Uenuku-mai-Rarotonga).

- The captain’s father (Houmatawhiti) and grandfather (Tuamatua) remained behind on their island homeland.

The genealogy table (Figure 1) indicates from the traditional narrative that six generations were living at the time of arrival in New Zealand. Tradition records the fourth generation Mōtai and Uenuku were born on the voyage to New Zealand. The genealogies of the Tainui and the Te Arawa provide a contextual and historical link between these individuals in Figure 1. Furthermore, the traditional narrative around key personnel of the Te Arawa, namely; Ngātoroirangi, Tia and Hatupatu, within the context of this paper, feature in determining a specific Gregorian departure date from Hawaiki (Tahiti) and an arrival date in New Zealand.

- Understanding the Genealogical Tables

Figure 2 table of genealogies (below) identify four generations aboard both the Tainui and Te Arawa on their arrival to New Zealand. The co-author Simmonds has extensive authoritative whakapapa, or tribal genealogies for both Tainui and Te Arawa that were analysed to identify a timeframe for determining an estimated time period of arriving. The analysis was then used to give a specific eclipse candidate that occurred during that time period. The co-author Simmonds is a direct descendant of both captains and to other members of each vessel. His descent is through his paternal grandfather, Tiaki Kereti, and Rangimahora Mete. Rangimahora Mete is a karanga-kuia, or traditional tribal grandmother, to Simmonds.

Figure 2 below links Tiaki Kereti and Rangimahora Mete (names at bottom of table) to both captains of the Tainui and Te Arawa. Both Tiaki Kereti and Rangimahora Mete have the same grandfather, Te Taute (Hare Teimana) who is also a direct descendant of both captains. Rangimahora Mete’s father, Heketoro, is also a direct descendant of captain of Te Arawa, Tamatekapua.

We show in Figure 2 genealogies spanning the years from 1300 AD to 1900 AD[9]. Each line is an ancestral name associated with this person’s whakapapa, or genealogy. The left-hand column represents a generation (of 25 years) and the right-hand column represents number of generations back from 1900. The shaded-area (top four lines of each genealogy) indicates four-generations of members on board the Tainui or Te Arawa who arrived in Aotearoa – New Zealand. These four generations must be considered when determining an estimated arrival period.

Fig 2. Whakapapa – Linear Genealogy from Tainui and Te Arawa members.

Year | Tainui 1 | Tainui 2 | Tainui 3 | Te Arawa 1 | Te Arawa 2 | Te Arawa 3 | |

1300 | Hoturoa | 25 | |||||

Hoturoa | Hotuope | 24 | |||||

1350 | Hoturoa | Hotuope | Hotumatapu | 23 | |||

Hotuope | Hotumatapu | Motai | 22 | ||||

1400 | Hotumatapu | Motai | Uetapu | 21 | |||

Motai | Uetapu | Rakamamao | 20 | ||||

1450 | Uetapu | Rakamamao | Kakati | Tamatekapua | Tamatekapua | Tamatekapua | 19 |

Rakamamao | Kakati | Tawhao | Kahumatamomoe | Kahumatamomoe | Kahumatamomoe | 18 | |

1500 | Kakati | Tawhao | Whatihua | Tawake | Tawake | Tawake | 17 |

Tawhao | Turongo | Uenukuwhangai | Uenuku | Uenuku | Uenuku | 16 | |

1550 | Turongo | Raukawa | Kotare | Rangitihi | Rangitihi | Rangitihi | 15 |

Raukawa | Takihiku | Kauwhata | Tuhourangi | Tuhourangi | Tuhourangi | 14 | |

1600 | Whakatere | Pipito | Wehiwehi | Uenukukopako | Uenukukopako | Uenukukopako | 13 |

Poutu | Tamatewhana | Tutete | Whakaue | Kiritai (w) | Whakaue | 12 | |

1650 | Huri | Maihi | Parekarewa (w) | Kaitapu | Hineau (w) | Tawakeheimoa | 11 |

Ahiroa | Pareunuora (w) | Ngatokowaru | Rangipunga | Pareunuora (w) | Rangiwewehe | 10 | |

1700 | Te Awa | Matau | Matau | Tiori | Matau | Kereru | 9 |

Te Ngue | Puauea (w) | Puauea (w) | Te Ngakau | Puauea (w) | Wehiwehi | 8 | |

1750 | Haehaekuku | Parehikanga (w) | Parehikanga(w) | Hoputu | Parehikanga (w) | Whatutapunui | 7 |

Hakunga | Kainganui (w) | Kainganui (w) | Paneturi (w) | Kainganui (w) | Ngarotu | 6 | |

1800 | Kapu (w) | Pahau | Pahau | Kapu (w) | Pahau | Whekiki | 5 |

Rauti (w) | Rauti (w) | Rauti (w) | Rauti (w) | Rauti (w) | Hikairoa | 4 | |

1850 | Hare Teimana | Hare Teimana | Hare Teimana | Hare Teimana | Hare Teimana | Atareta (w) | 3 |

Tawhai | Tawhai | Tawhai | Tawhai | Tawhai | Heketoro | 2 | |

1900 | Tiaki Kereti | Tiaki Kereti | Tiaki Kereti | Tiaki Kereti | Tiaki Kereti | Rangimahora (w) | 1 |

- Genealogies in Determining the Arrival Time

When considering an arrival period using genealogical tables it is important to consider all the associated generations present during the event. In this case the traditional narrative maintains that four generations were on board both vessels when they arrived in New Zealand. Therefore, the arrival period must consider the birth period of the great-grandchildren born on the journey to New Zealand as a key determining factor. The new estimated period will be derived when we consider the archaeo-astronomical evidence and determine which solar eclipse event was witnessed by members of the Te Arawa vessel. The solar eclipse event will provide a high degree of certainty to extrapolate a new estimated Gregorian arrival date.

A Gregorian arrival timeframe can be estimated with a high degree of certainty with closer analysis of the genealogical lines. Combining the genealogies with the all of the living generations during the period of migration can establish a likely timeframe of departure and arrival to less than a generation. Therefore closely analysing the generational living cohort involved during the migration period, according to the traditional narrative, provides a degree of certainly in determining an arrival period. Prior to this research a Gregorian departure and arrival date was unknown.

- Six Living Generations During the Migration Period

In this section we explain why an assessment of six generations must be considered when estimating a possible arrival period. On their departure from Hawaiki (Tahiti), according to traditional narrative, Tamatekapua’s father, Houmaitāwhiti and his grandfather, Tuamatua, were still alive (A.W Reed, 1977:101; W.E Gudgeon, 1894). The six generations of great-grandparents, grandparents, parents, children and grandchildren must have spanned 90 years or more.

Utilizing this genealogical information, the departure from the Eastern Pacific and arrival in New Zealand can be narrowed down to a very specific timeframe, of much less than a generation. This narrow timeframe limits the arrival and departure period to a very narrow window of opportunity that can support a specific Gregorian date.

- Generation Disparity Between Genealogies

The substantial generational disparity between the genealogies of the Tainui and Te Arawa descent lines can be largely ignored due to a key factor. That is, both vessels left together and arrived together in New Zealand which essentially aligns the generations. The disparity can therefore be ignored.

In pre-European times traditional genealogies were all passed down from generation to generation by rote learning and held in the memory of knowledge-experts, the tohunga, or the tribal priests. Authenticity depended on consistency across many different tribal sources in New Zealand and East Polynesian island sources. In the table there is a significant difference in the number of generations descended from each captain. The disparity in generations between them show variations spanning 10 generations, or 250 years.

The traditional narrative maintains that both vessels left together and arrived together. Leaving and arriving together aligns the generations as contemporary to that period. Furthermore, the father and grandfather of the captain of the Te Arawa waka were still alive on departure. Moreover, the captain of the Te Arawa became a great grandfather on the voyage to New Zealand, with the birth of Uenuku-mai-Raratonga, meaning Uenuku from Rarotonga (born at Rarotonga, Cook Islands. [10]Rarotonga was a stop-over destination on their journey to New Zealand. This birth created the sixth living generational-cohort that implies the time period for the departure and arrival provides a very narrow window for this event to take place in terms of genealogies. This helps reinforce a specific timeframe period for the historical migration event.

- Traditional Narrative

This paper argues that a well-known legend of Hatupatu ties in with other members of the Te Arawa vessel who were exploring the central volcanic plateau at the same time as an historical solar eclipse occurrence. Although the 21st century is well into the second decade, many Māori still vehemently hold on to superstitions that emanate from these classical times. These early Polynesian ancestors of Māori were traditionally deeply superstitious. Many of these early superstitions can be directly linked back to the period of the original voyagers in the “Great Fleet” and their exploration of the central volcanic plateau.

Traditional legends and narratives describe historical events that are retained in stories, songs, proverbs and chants. One such narrative is that of Hatupatu and the bird-women is deeply embedded in the memory and place names in the Taupō central volcanic region (Harris et al, 2013). The Hatupatu legend and the rock itself are significant to the tribes of Tainui, Te Arawa and Tūwharetoa, the traditional people of the region.

- Identifying a Gregorian arrival date

- Eclipse Events – Identifying a solar eclipse event

Identifying a specific solar eclipse event associated with traditional narratives involves a process of eliminating other possible eclipse events. If the historical narrative describes a solar eclipse, therefore archaeo-astronomical research indicates that there are four possible candidate solar eclipse events between 1350 AD and 1450 AD. The critical eclipse event suggests it passed over the central Taupō volcanic region within the timeframe associated with the arrival of the “Great Fleet”.

Therefore, the mostly likely event infers that the intrepid explorers from the Te Arawa witnessed a solar eclipse on one of the following dates[11]:

- 15 June 1368: Early morning, Far North, North Island

- 9 October 1409: Afternoon, Volcanic Plateau, North Island

- 2 January 1424: Afternoon, Southland, South Island

- 11 December 1433: Early morning, Cook Strait, North-South Island

We can compare the likelihood of these events by analysing a number of factors that will eliminate three eclipses and highlight the most prominent eclipse candidate. The close analysis of the 1368, 1424 and 1433 eclipses events can be discounted and not supported by key factors such as: the geographical location of the area of totality and flight path is off shore; too early or late for a six-generational living cohort; the summer seasonal event is problematic to the traditional narrative; the chronological window is poor. Therefore, an arrival in these three periods must also be dismissed.

- Candidate Eclipse – 1409 AD

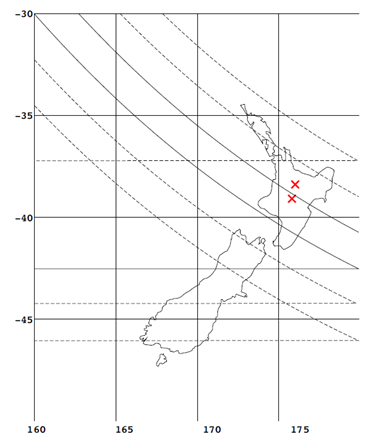

Historical narrative and legends passed down by Māori suggests that a very deep eclipse was observed. The total eclipse of 9 October 1409 has a number of key features that identifies it as the preferred candidate. It should be noted that the path of totality travelled over the central volcanic plateau on that fateful day. The flight path of the solar eclipse of 9 October 1409 AD is shown in Figure 3 below.

Fig 3: ∆T – 600 secs – 9 October 1409 AD

(‘X’ indicate suggested location of explorers during eclipse)

Two of the intrepid explorers, Ngātoroirangi and Tia, were within the area of totality at Rangipō (near Turangi) and on the shore of Lake Taupō. Hatupatu appears to be at Atiamuri and on the boundary limits of totality. Traditions tells us the day was already dark and bleak, heavily overcast, cold with possible snow and sleet (A.W Reed, 1977: 119). This overcast gloom and darkness would have intensified the tapu, or sacredness of this unexpected supernatural effect of an eclipse’s shadow of totality. On this basis the key archaeo-astronomic event strongly supports the 1409 historic solar eclipse that was witnessed by the explorers from Te Arawa.

The October 1409 eclipse event correlates with the arrival seasonal conditions, the genealogy chronological factors, the exploration timing, including departure and arrival dynamics and historical narrative.

- Determining a Possible Arrival and Departure Period

The basis of this research is that a full solar eclipse was witnessed by members of the Te Arawa waka in October 1409. This being the case, the Te Arawa and Tainui, possibly arrived in New Zealand eleven months earlier, in mid-December 1408. This arrival period is supported by tradition, whereby the voyagers made landfall on the East Coast of the North Island. At this time the native pōhutukawa were in full bloom signaling summer (D.M Stafford, 1967:428).

The December arrival supports a departure in November of that year from their traditional homelands in Central Eastern Polynesian. The journey is estimated to have taken approximately 30-26 days according to Tainui tribal tradition and narratives (P.T.H Jones, 1995:52). Therefore, a December 1408 arrival in New Zealand places their departure in November 1408 AD.

- Determining a Specific Gregorian Date of Departure

The task at hand is to determine an extrapolated Gregorian departure date. Tradition tells us that Tainui and Te Arawa departed from Hawaiki (Ra’iātea, Tahiti) in French Polynesia (P. Buck, 1938:271; A.W Reed, 1977:99). The vessels then sailed to Rarotonga (in the Cook Islands) before finally setting off for New Zealand (P.T.H Jones, 1995:32). The fixed Gregorian date of the solar eclipse, 9 October 1409 AD was also a new moon, or Mutuwhenua, (lunar-day 30, or 29) that correlates to the traditional Māori luni-solar calendar system[12]. Tradition also suggests that both Tainui and Te Arawa arrived in December, or mid-summer 1408 AD.

The traditional narrative says that the time it took to sail Tainui from their Eastern Polynesian home was approximately 26 to 30 days (P T. H. Jones, 1995:52). This places their departure in November 1408 AD. The traditional lunar day of departure from Hawaiki (Tahiti) was Orongonui ō te tau ururoa (P. Buck, 1938:271; M. Winiata, 1950:5)[13]. That is, Orongonui is the 27th lunar day of the traditional Polynesian calendar system. Therefore, the 27th lunar day, or Orongonui, corresponds with the 15th November, 1408[14].

That is, the extrapolated Gregorian date of departure, from Hawaiki for both Tainui and Te Arawa, was the 15th November, 1408.

- Arrival Date and Departure Date from Rarotonga

The original departing site Hawaiki (Ra’iātea, Tahiti) in French Polynesia is approximately 800 km or 500 nm from Rarotonga. This is a modest distance and could be sailed easily by these ocean voyagers within a few days[15]. Tainui and Te Arawa departed Hawaiki (Ra’iātea, Tahiti) on 15th of November 1408 AD. After about three days at sea they arrived in Rarotonga. Tainui and Te Arawa stayed several days in Rarotonga before setting off again for their final destination, New Zealand. The departure date of both Tainui and Te Arawa from Rarotonga, was on the traditional lunar day of Oo-Uenuku, day-four of the calendar (P.T Jones, 1995:30). The traditional lunar day Oo-Uenuku (of Uenuku) is recognized in the birth of the great, great grandson of the captain, Tamatekapua, and named Uenuku-mai-Rarotonga, or Uenuku born at Rarotonga. Uenuku’s name possibly celebrates on the day the Te Arawa waka departed for New Zealand.

The extrapolated Gregorian date of departure from Rarotonga (Cook Islands) of both Tainui and Te Arawa was the 22nd November 1408.

- Gregorian Arrival Date in New Zealand

The arrival in New Zealand by both the Tainui and Te Arawa has been debated for the past 600 years. Tainui traditions state that the journey took 26 days (P T.H. Jones, 1995:52). The traditional narrative has the sailing vessels travel via Rangitahua, Raoul Island in the Kermadec Island group (Te Rangi Hiroa (Buck), 1977:46). The Kermadec group lies 800 km, or 500nm, north-east of New Zealand and a short final journey. Hoturoa Kerr, a current traditional contemporary sailing expert has taken 12 days to sail directly from Rarotonga to New Zealand[16]. Therefore the traditional recorded time of 26 days strongly supports a detour for Tainui and Te Arawa via Rangitahua, Raoul Island in the Kermadec group before their arrival on the East Cape in New Zealand.

The Tainui arrived in New Zealand during the dark of the moon, the food was planted, which amounts to 26 days from Rarotonga. Tainui left Rarotonga on 22 November 1408. It took 26 days to travel puts the traditional arrival date at Mutuwhenua, a new moon phase, in the month of December (P.T H. Jones, 1995: 52).

The extrapolated Gregorian arrival date for Tainui, was a new moon phase, or the 18th December 1408 AD. That is, Tainui arrived on the 18th December 1408. The Te Arawa arrived on the seventh lunar moon, in the Tamatea lunar phase, a first quarter phase (D.M Stafford, 1967:17). The extrapolated Gregorian date for the arrival of Te Arawa is the 26th December 1408.

- Complementary Narrative

- Eastern Polynesia Departure Time

There are key seasonal and astronomical markers that strongly support a departure in mid-November 1408, from Eastern Polynesian, in the narrative that can help establish a more accurate date. Arrival in New Zealand in the height of the summer is recognised as traditional stories tells of the “Great Fleet” people observing the pohutakawa flower that blooms in December. This begs the question, is there similar narrative that describes the departure time from the islands of East Polynesia that complements this seasonal period?

Major Eastern Polynesia celebrations are held that are signified with the evening rising of Matali’i (Pleiades) in November. Throughout Eastern Polynesia the evening rising of Matali’i coincides with the seasonal arrival of abundant fish species in the surround seas. This seasonal abundance begins with whitebait, followed by the Pacific bonito fish[17].

The traditional departure date that aligns with the arrival time in New Zealand and adjusted for travel time was ‘Orongonui ō te tau ururoa’. The month ‘te tau ururoa’ means in Tahitian ‘the long-bread fruit season’, or the fruiting of breadfruit, which aligns with November. Thus a departure date from Hawaiki (Tahiti), in November of 1408, coincided with an abundance of fresh fish, breadfruit and food to stock their voyage supplies before departing. These key seasonal markers and astronomical markers strongly supports a departure in mid-November 1408 AD.

- Discussion and Conclusion

- Traditional astronomical direction to New Zealand

This research challenges the historic arrival date 1350AD of the Māori on the “Great Fleet” to New Zealand. This research suggests that the most likely arrival Gregorian date of the Te Arawa sailing vessel to New Zealand based on the presented evidence is the 26th December 1408. Furthermore the most likely Gregorian date of the Tainui vessel arriving is 18th December 1408. This correlation of evidence has been gathered from information of deriving the Gregorian date by combing with the traditional Maori luni-solar calendar system as discussed elsewhere in this paper (see Section 4.5).

According to the traditional narrative the Polynesian navigator, Kupe, was apparently the first to have discovered New Zealand. On his return to Hawaiiki (Tahiti) Kupe gave directions back to New Zealand as a little to the left of the setting sun, the moon and Venus in the months of November and December (P. Buck, 1938: 269, E. Best, 1955: 36, A.W. Reed, 1977: 104). The Eastern Polynesians followed Kupe’s directions in the “Great Fleet” back to New Zealand[18].

The nature of Kupe’s astronomical directions that include Venus appearing in the summer is significant to the timing of the “Great Fleet” migration. In mid-December 1408 the lunar phase was a new moon and the planetary motion and direction of Venus in mid-December 1408, above the Western horizon, is highly visible, again is a key directional finder. Importantly Venus was in a superior-conjunction position and sets in the evening at the same latitude as the summer sun in the South-West. This planetary conjunction occurs on an eight-year cycle[19].

The Polynesian star-navigator experts would have been aware of this eight-year, short term, astronomical cycle. The setting sun, moon-cycle and Venus would have been easily visible by mid-December 1408 over the Western horizon of New Zealand as an astronomical navigating beacon. This research and study advocates that Kupe was a contemporary of the “Great Fleet”. Moreover, this research contends that Kupe explored New Zealand within the previous decade of the “Great Fleet” migration (L. Kelly, 1949, D.R Simmons, 1967).

- Maritime Navigational Markers

The navigational expertise of the traditional Polynesian seafarers was extraordinary. The use of star knowledge has been acknowledged by many writers. Furthermore, their ability to navigate by meteorological and climatic conditions has also been applauded by writers (D. Lewis, 1977, 1978, J. Evans, 2009). During this research we found clear evidence of their ability to use previously unrecognised navigational skills and expertise.

According to the traditional Tainui narrative the “Great Fleet” predominately arrived at Whangāparāoa on the East Cape of the North Island. There is strong maritime and oceanic evidence that traditional navigators used a ‘shadow effect’ that projects calmer sea-swells North-Eastwards from New Zealand[20]. The ‘shadow effect’ extends North-East towards the Kermadec Islands and Tonga. The traditional expert navigators will recognise the calm sea ‘shadow effect’ and follow the edge of the ‘shadow’ to an unseen island, in this case, New Zealand.

Tradition records that most of the voyaging vessels landed on the East Coast suggesting they followed the ‘shadow-effect’ projected northwards from the East Cape (A.W. Reed, 1969:169). Furthermore, the East coastline of New Zealand is over 2,000 km long and very difficult to miss (D. Lewis, 1978). Therefore, the Whangāparāoa near the East Cape of the North Island is the mostly likely arrival destination for the majority of the “Great Fleet”.

- The Great Fleet

This research found that final migration push from the Eastern Polynesian was by a “Great Fleet” of 10 or more ocean-going voyagers carrying upwards of several hundred individuals to settle New Zealand. The traditional narrative tells us that the “Great Fleet” contained about a dozen waka, or more, that arrived in that summer of 1408. Importantly, although the idea of a “Great Fleet” was dismissed by historians (M. King, 2003:46), this exodus from the Pacific islands was led by the captains of the fleet who brought their elders, wives, grandchildren, great grandchildren and extended families. This was a well-planned voyage of settlement that also brought their religion, culture, dialects along with their animals, plants, faith and most of all their hopes. Most important of all they brought their experts, navigational experts, knowledge-holders, genealogists, horticulturalists, astronomers, military planners, town planners, priests and spiritual leaders.

To conclude this was a unique migration for it was the last. This was the final “Great Fleet” that saw a mass migration to settle this last great land-mass on planet Earth that is New Zealand. There are no other traditional narratives indicating that further migrations followed the “Great Fleet”. Moreover, this final journey by Polynesians carried their “Alexandria library” of East Polynesian oral history, education, religion, science, technology and knowledge.

- The Convergence of the Natural and Supernatural Phenomena

The spiritual power of Ngātoroirangi, the tohunga, spiritual leader and navigator and the solar eclipse event, by themselves, was not the only factor that promoted the impact of the occasion on the newly arrived Polynesian visitors. There are several key factors that converged on that eventful day. The events were amplified by a mix of natural environmental, astronomical combined with the supernatural events.

The perceived supernatural was helped by a large measure of traditional tapu, or sacredness, which was entrenched within the culture of the intrepid explorers. Tapu literally means, prohibition by the laws of the native gods (S. Mead, 1984:91).

The natural archaeo-astronomical events were the combined effect of the solar eclipse in conjunction with a key lunar phase, a new-moon phase on that day in October 1409. The new moon phase is called Mutuwhenua. The new moon phase, the end of a traditional lunar month, is a spiritual day of reflection, quiet contemplation and is tapu, sacred, to the native mind[21].

Importantly, to the explorers, a full solar eclipse was an unexpected and an unnatural event. This unexpected occurrence reinforced the underlying ethos of tapu, or sacredness and utter fear embodied in the day. Adding to the native mind on this ominous day was the environment; the cold, bleak and miserable stormy weather. Psychologically the culture and new moon phase had pre-conditioned the emotions of the early explorers into a state of fear and awe. The unsuspecting travelers would not have seen the eclipse event, except they experienced e tau ana te pō, or Taupō; an unnatural deep darkening of the sky over them. The unexpected mid-afternoon solar eclipse intensified the utter fear of the native explorers which helped to entrench the occasion into native legends and stories, including the fear and superstition, which still exists today.

This research explores the idea that a historical solar eclipse event is represented in traditional narratives of the Hatupatu legend and the legendary narratives of naming Lake Taupō and the Rangipō plateau indicates a solar eclipse event. Thus the solar eclipse event helped to determine a new extrapolated Gregorian arrival date for the Tainui and Te Arawa waka to New Zealand.

- Conclusion

Based on the stories handed down by word of mouth from one generation to the next there is a very strong argument to suggest that a “Great Fleet” arrived in New Zealand in the summer months of 1408. They set out from their island homes just after the celebrated evening rising of Matali’i (Pleiades) a time of the year for bountiful food supplies in Hawaiki (Tahiti). They took so many days to sail here, via Rarotonga and the Kermadec Islands and landed when the pōhutukawa were in full bloom. After acclimatizing and improvising warmer clothing, in their first New Zealand winter, some of the leaders decided to explore the central volcanic plateau. Travelling into the central volcanic plateau of the North Island the intrepid explorers would name geographical landmarks that continue to be used to this day. During this time they were overtaken by a solar eclipse event from which the Hatupatu legend and phenomenon of Taupō and Rangipō, the darkening skies, received their geographical names.

This archaeo-astronomical event which occurred on the 9th October 1409 warrants a rethink about the arrival time of the Tainui and Te Arawa waka to New Zealand, including the final ‘Great-Fleet’ mass migration and settlement. This new arrival period in the first decade of the 15th century is supported by genealogical evidence and a host of other complementary evidence. Moreover it is strongly embraced in Māori and Eastern Pacific customs and traditions that have survived for centuries. The earlier arrival date of 1350, based on mathematical manipulation of whakapapa or genealogical lines, seems haphazard and fanciful in comparison.

Finally, having now decoded the chronology of the previously proved the fact of the journey, made using a host of traditional technologies which we include in mātauranga, that the accomplishment of our migration by knowledge and plan is largely unknown or ignored by Western science, then and possibly now, is inexcusable. However, the intrigue behind the historical journey, the navigational skills a host of technical skills and spirituality, is unique. Furthermore, the journey was much more fascinating than this research can ever cover with respect and dignity.

- Acknowledgements

This is to acknowledge the scientific support of astronomers Kyotaka Tanikawa and Mitsuru Sōma of the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan. Tanikawa-san, as a co-author, together with Sōma-san’s invaluable technical input as international collaborators have been pivotal to this research. Without their collective support, scientific direction and patience this research may not have eventuated. The co-author Simmonds and the Society of Māori Astronomy, Research and Traditions Inc (SMART) are deeply indebted for their help. This also is to acknowledge the academic support and encouragement of Pauline Harris of the University of Victoria of Wellington, and chairperson of SMART, New Zealand. And finally to the many tribal elders of Raukawa whānui and other tribal elders for sharing their traditional genealogies, wisdom and knowledge that reach back 600 years to their voyaging ancestors of the “Great Fleet”. Nō reira, ka nui te mihi aroha ki a koutou katoa.

Bibliography

Best, Elsdon, 1955: The Astronomical Knowledge of the Māori. Dominion Museum Monograph No. 3, Government Printer, Wellington, New Zealand.

Bridgman, Howard A. 1983. Could Climatic Change Have Had an Influence on the Polynesian Migrations? Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 41(3–4): 193–206.

Buck, Peter H. 1938. The Vikings of the Sunrise. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott.

Condliffe, J.B. 1971. Te Rangi Hiroa, The life of Sir Peter Buck. Christchurch: Whitcombe & Tombs.

Cowan, James. 1925. Fairy Folk Tales of the Maori. Auckland: Whitcombe & Tombs.

Cumberland, Kenneth B. 1981. Landmarks. Edited by Reader’s Digest Services Pty Ltd. Surry Hills, Australia: Reader’s Digest.

Evans, Jeff. 1998. The Discovery of Aotearoa: Auckland: Reed.

Evans, Jeff. 1997 [2009]. Ngā waka o Neherā: the First Voyaging Canoes. Auckland: Libro International.

Grace, John Te H.G. 1959 [1970]. Tūwharetoa, The History of the Māori People of the Taupō District. Wellington: A.H & A.W. Reed.

Grey, George. 1988. Legends of Aotearoa. First published 1855 under another name. Hamilton, N.Z.: Silver Fern Books.

Gudgeon, W.E. 1894. Maori Migrations, No II. Journal of the Polynesian Society 3(1): 46–51.

Harris, P., Matamua, R., Kerr, H., Smith, T., Waaka, T,. 2013. A Review of Māori Astronomy in Aotearoa-New Zealand. The Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage, 16(3), 325-336.

Hiroa, Te Rangi (Peter H. Buck). 1949 [1977]. The Coming of the Maori (2nd ed.). Wellington: Whitcoulls Limited.

King, Michael. 2003. The Penguin History of New Zealand. Auckland: Penguin Books.

Lee, Michael. 2018. Navigators & Naturalists: French Exploration of New Zealand and the South Seas (1769–1824). Auckland: Bateman Books.

Lewis, David. 1977. From Maui to Cook: The Discovery and Settlement of the Pacific. Sydney: Doubleday Australia.

Lewis, David. 1978. The Voyaging Stars: Secrets of the Pacific Island Navigators. Sydney: Collins.

Mead, Sidney Moko. 1984. Customary concepts of the Maori: a Source Book for Maori Studies Students. Second revised edition. Wellington: Department of Māori Studies, Victoria University of Wellington.

Mitchell, J. H. 1944 [2011] Takitimu. Cadsonbury Publications (2011). A.H & A.W. Reed, Wellington (1944).

Reed, A.W. 1977. Treasury of Māori Exploration, Legends Relating to the First Polynesian Explorers of New Zealand. Wellington: A.H. & A.W. Reed.

Simmons, D.R. 1976. The Great New Zealand Myth: a Study of the Discovery and Origin Traditions of the Māori. Wellington: A.H. & A.W. Reed.

Sorrenson, M.P.K. 1979 [1983]. Maori Origins and Migrations. University of Auckland.

Stafford, D. M. 1967. Te Arawa: A History of the Arawa People. Wellington: Auckland Reed.

Tanikawa Kiyotaka 谷川清隆 and Sōma Mitsuru 相馬充. 2010. ‘Amana-Iwato’ nisshoku kōho ni tsuite『天の磐戸』日食候補について (On Candidate Eclipses of a Supposed Eclipse in Myth ‘Amano-Iwato’). Kokuritsu temmondai hō 国立天文台報 (Publications of the National Observatory of Japan) 13: 85–99.

Jones, Pei Te Hurinui. 1995. Ngā Iwi o Tainui: nga koorero tuku iho a nga tuupuna (The traditional history of the Tainui people). Edited by Bruce Biggs. Auckland: Auckland University Press.

Whatahoro, H.T. 1913–1915 The Lore of the Whare Wananga, or, Teachings of the Maori College on Religion, Cosmogony and History. Translated by S. Percy Smith. New Plymouth, N.Z.: Polynesian Society.

Williams, Herbert W. 1975. A Dictionary of the Māori Language. 7th ed. Wellington: Government Printer.

Conference Proceedings

Sōma, M., Tanikawa, K. (ed).: Proceedings of the fourth symposium on the “Historical Records and Modern Science”, 2014.

Nakamura, T., Orchiston, W., Sōma, M., Strom, R (ed).: Proceedings of the seventh International Conference on Oriental Astronomy (ICOA-7), “Mapping the Oriental Sky” (2010).

Sōma, M., Tanikawa, K.: Proceedings of the sixth symposium on the “History of Astronomy”, (2017).

Media

Rolls, L.: Tupaia’s Endeavour, (a television documentary), Episode 1 of 3. Producer: Island Productions 2016, New Zealand (2016).

Winiata, M.(ed.).: Tainui Sexcentennial Canoe Celebrations 1350 – 1950. Souvenir Brochure. New Zealand: Turangawaewae Māori Adult Education Committee and Tainui Sexcentennial Canoe Celebrations (1950).

Wolfram Alpha LLC.: http://www.wolframalpha.com/examples/LunarPhases.html. Database: Lunar Phases and solar eclipses (2018/11/12).

Primary sources – Personal manuscripts (unpublished)

Rangimahora Mete. Personal manuscripts, oral information of Tainui, Raukawa and Te Arawa whakapapa. (1991)

Rangipapanui Te Kaponga. Personal Manuscript (Copy): Genealogies of Tainui, Maniapoto, Raukawa, Te Arawa whakapapa (c1912).

Piripi Kereti (Simmonds-Teimana). Personal manuscripts, genealogies, (1974), Raukawa (tribe), South Waikato (region) (1970)

Whanaupani Kereti (Simmonds-Teimana). Personal manuscripts. Raukawa (tribe), South Waikato (region) (1970)

Te Hiko, N. Otaki and Waikato Native Land Court Minutes, 1860-1909. Transcribed Native land court records (2007).

Te Ururoa Flavell.: Personal manuscripts of Te Arawa whakapapa (1980)

Secondary sources: Oral sources – traditional knowledge holders

Begbie, Ruthana Okeroa: Raukawa (tribe), Putaruru, South Waikato

Drollett, Hinano (Astrid): Tahiti, French Polynesian

Makiha, Rereata: Te Māhurehure (tribe), Auckland, Far North

Nicholson, Iwikatea: Raukawa/Toarangatira (tribes), Otaki, Manawhēnua

Waaka, Rupene: Raukawa (tribe), Otaki, Manawhēnua

Wereta, Hoani: Tūwharetoa/Raukawa (tribes), Taumarunui/Taupō

References

[1] The Society of Māori Astronomy Research and Traditions (SMART) Inc, New Zealand ockie.simmonds@smsa.nz

[2] National Astronomical Observatory of Japan, Osawa, Mitaka, Tokyo, Japan

tanikawa.ky@nao.ac.jp

[3] Co-author Simmonds attended the presentation by Tanikawa-san at the ICOA-8 conference in China, March 2014. Taniwaka-san’s presentation and findings initiated this research.

[4] Personal communication: Rev Rahu Katene, 31/03/2018. Rev Rahu Katene is a descendant of Ngātoroirangi and his wife Kearoa who travelled on the Te Arawa to New Zealand.

[5] Hatupatu Legend: The legend has been Westernised for reader consumption over the past 150 years. However, the Māori narrative records that Hatupatu story is traditionally and historically different to the Western version.

[6] Hatupatu – geographical location: The Hatupatu rock-cave location stands on the edge of the area of totality during the solar eclipse (Pers com, Tanikawa san, email: 23 May 2015).

[7] Refer, Gudgeon (1894: 46-51). Journal of the Polynesian Society (Extract) for whakapapa.

[8] Winiata & Jones give two different departure dates – either 26 days or 30 Days. Jones is 26 Days from Rarotonga. Winata is 30 Days from (Hawaiki (Rangiatea). This aligns with both departure dates.

[9] Genealogy information sources: Private manuscripts from: Piripi Kereti (Simmonds-Teimana), N. Te Hiko, R. Waaka, Te Kaponga, Rangimahora; Te U. Flavell.

[10] The date of birth on ‘Uenuku’ also represents the departure date. That is the 4th lunar day of the traditional native lunar calendar. That name ‘Uenuku’ is still used by to represent the 4th lunar day by Tainui and Te Arawa descendants.

[11] Person communication: Tanikawa, K., Emails 2014 to 2018

[12] Ref: Wolfram Alpha LLC.: http://www.wolframalpha.com/examples/LunarPhases.html.

[13] Personal communication: Hinano Astrid Drollet, email: 26/11/2016. Drollet, a linguist from Tahiti identified the correct spelling and meaning of ‘te tau ururoa’ (the long breadfruit season). Māori had forgotten the name ‘uru’ for breadfruit because it failed to grow in New Zealand. However the name ‘uru’ is known in traditional Māori waiata, or songs. Uru, or kuru (a dialectal form) means breadfruit.

[14] Ref: WolframAlfa, Computational database: https://www.wolframalpha.com/ Phases of the Moon application to acquire extrapolated Gregorian calendar dates.

[15] Personal communication: H. Kerr, 11/09/2017

[16] Personal communication: H. Kerr, 11/09/2017

[17] Personal communication: H. Drollet, email 18/11/2016.

[18] Historians like Percy Smith in the early 20th Century had placed Kupe’s discovery in 950 AD by genealogical evidence that has been largely discredited (P. Buck, 1938; D.R Simmons, 1967).

[19] Personal communication: Tanikawa san and Sōma san, 22/10/2018.

[20] Personal communication, E. Brunstrum, 28/3/ 2019

[21] Personal communication: Whanaupani Kereti (Simmonds Teimana).

FIGURE 1

The two genealogies outline the relationship of personnel on both vessels. The names from Hoturoa and below arrived on the Tainui waka. The names below Rakauri and Houmaitawhiti all arrived in New Zealand on Te Arawa.

FIGURE 3

The flight path of the solar eclipse of 9 October 1409 AD is shown in Figure 3 be-low.