Dr Matiu Prebble

Friday 23.08.19 Session 4: Dr Matiu Prebble session on “The Microscopic Ecology of Early Voyaging”

Critiquing Cook's Observations of Māra Māori Cultivations in Northern Aotearoa New Zealand in 1796 using Fossil Evidence for Korare - Leafy Green Vegetables

Dr Matiu Prebble1, 2, 3

1Te Kura Aronukurangi/School of Earth and Environment, College of Science, University of Canterbury, Christchurch 8041, New Zealand

2Te Pūnaha Matatini, Auckland 1011, New Zealand

3Department of Archaeology and Natural History, School of Culture, History and Language, College of Asia and the Pacific, The Australian National University, Canberra, ACT 2601, Australia

Dr Matiu Prebble has served in research at New Zealand and Australian universities, solving problems of extinction and introduction of plants, wild and domestic, often linked to the arrival and settlement of people. His forty-odd publications range from studies of pollen and leaf wax to the wider implications of human impact on the plant environment and on climate change. Prebble is an archaeologist in this sense that his particular practice of archaeobotany tracks changes in flora, related to human occupation, from pre-settlement through prehistoric, into the historic. For us he focuses this knowledge on how the Māori lived with their plants at the moment Cook saw them, in the context of what a paleobotanist can tell from the physical remains of that time. Historians will particularly appreciate the Appendix, on Aotearoa’s relationship to the European mariner’s historic problem of antiscorbutics.

Abstract

Numerous commensal species were introduced from the small tropical Pacific Islands to the cool-climate of continental Aotearoa on the Māori ancestral voyages. More is known about introduced domesticates such as the kurī Canis familiaris and kūmara Ipomoea batatas, due to their economic and cultural importance. Observations of cultivated plants by James Cook and the crew of the Endeavour between 1769-70, including of kūmara, taro Colocasia esculenta, uwhi Dioscorea alata, aute Broussonetia papyrifera, and tī karo Cordyline fruticosa, continue to influence ideas on traditional Māori cultivation practices. Outside of the kūmara cultivations observed by the Endeavour crew, who were visiting at the beginning of the cultivation cycle, much of the vegetation around kāinga/villages that were thought of as ‘wild’ were likely to have been fallow cultivations. Furthermore, the role of lesser-known commensal plants including celery, cress and sow-thistle collected during their visits to Māori settlements, or areas they described as ‘wild’, remains ambiguous. These plants were and continue to be used as korare leafy green vegetables, or as traditional rongoa medicine. Fossil records of seeds and pollen of korare species, extracted from buried wetland soils associated with Māori cultivation systems from the northern offshore islands, provide evidence that can be used to further elucidate the Endeavour observations. By focusing on the journals and plant collections of the Endeavour crew, archaeological and fossil remains, as well as traditions of plant use, an outline of the role of korare in traditional Māori cultivation is provided. Fossils of many of these plants including some that may have been introduced to Aotearoa, indicate they were once common on the offshore islands, where they may have been translocated from the mainland. These species are now absent on most of these islands, and many are regarded as being at risk of extinction from modern land-use practices and exotic invasive species. The abundance of fossil material recorded in buried cultivated soils, indicates that the economic purview of Māori and emphasis on cultivation in the north was not limited to kūmara and taro.

Introduction

Māori are descendants of agricultural peoples who independently domesticated animals (e.g. chickens Gallus gallus, pigs Sus scrofa, and kurī dog Canis familiaris) and plants (e.g. taro Colocasia esculenta, uwhi yams Dioscorea sp., hue bottle gourd Lagenaria siceraria and aute paper mulberry Brousonettia papyrifera), then transported and adapted these commensal species (co-habiting culturally modified ecosystems with people such as houses and cultivation systems) across the Pacific Islands over at least the last three millennia. These species had, and continue to have cultural significance to Pasifika and Māori societies, whereby husbandry and cultivation imbues connection to place and ngā tupuna ancestors. The significance of these species has been recorded in oral traditions and early ethnographic observations. Archaeological studies are further substantiating their cultural status, identifying former areas in the landscape, now occupied by cities, farms or forests.

Because of their cultural importance, it is puzzling that the spread of some of the introduced commensal species was limited, particularly the domesticated animals, to the most remote islands, including the Hawaiian Archipelago, Rapa Nui, and Aotearoa (Anderson 2009). One of many possible explanations is that these and other tropical species were poorly adapted to more adverse cool-temperate conditions of Aotearoa, where pigs and chickens either failed to survive or were not introduced. The prevalence and apparent high economic value of indigenous moa (Dinornithiformes) and other ground dwelling birds, evident from archaeological middens (Wood et al. 2016), may have meant that there were few incentives to retain the tropical adapted chicken. Similar ideas have been put forward as to why the pig did not survive on many Pacific Islands, including in Aotearoa (Anderson 2009; Clark et al. 2013). One hypothesis is that large and/or feral pig populations either threatened the more important crop production systems, or that the supplementary food required to sustain herds was an economic burden in these unfamiliar and remote islands (Anderson 2009). There are also other cultural explanations, some that are partly informed by oral traditions, but otherwise remain speculative in wait of further supporting evidence.

Here, I provide an outline of the growing body of evidence available from multiple sources, including oral traditions, archaeology, palaeoecology, as well as early European observations, to understand the origins, movements and continuing traditions of cultivation of other lesser-known commensal species, domesticated or ‘wild’, and their role in Māori cultivation practices. My aim is to build on the current understanding of the dynamics of traditional Māori horticulture, as well as to identify gaps in knowledge. The potential for re-defining the scale and diversity of traditional Māori horticulture based on fossil and other evidence is highlighted. These lines of evidence are also used to further critique the distorted observations of Māori horticulture by James Cook and the Endeavour crew in 1769-1770.

Commensal plants

This cultural prominence of taro and kūmara, coupled with the different ecological requirements of each species, meant that the long-standing horticultural practices developed over generations on the small islands of tropical Hawaiki, took on new forms upon arrival in Aotearoa. Not only were specific environments transformed or built to sustain taro and kūmara, but this transformation in many cases enhanced the growth of a wide variety of introduced, indigenous or endemic (found only in Aotearoa) plants. The provenance or origin of some of these plants is unknown, but cultural connections are inferred from oral traditions, and the contemporary use of these species by Māori for food as korare leafy green vegetables or as rongoa medicine. However, some of these plants also have ‘weedy’ characteristics with no apparent economic or cultural value, and most likely hindered the production of target crop plants such as kūmara (Prebble et al. 2019) (see Appendix for a summary of the evidence for celery, water cress and sowthistle species). Further complicating our understanding of these korare and otaota weeds is that many of them can or are currently found in ‘wild’ populations, growing in highly disturbed ‘natural’ environments such as on coastlines or on braided riverbeds. In some areas where they were previously abundant, they are now absent, often outcompeted by more recent introductions of invasive plants, and are now regarded as threatened or at risk of extinction (https://www.nzpcn.org.nz).

Early European accounts of Māori cultivation systems and commensal plants

Many of the early descriptions of Māori cultivations or māra recorded by Europeans have been discussed elsewhere (Best 1925; Leach 1984, 2005; Salmond 1991). The implications of these accounts for understanding what commensal plants may have been introduced during initial Māori settlement of Aotearoa have also been discussed, including the status of some of these species as ‘weeds’ (Leach 2005; Prebble et al. 2019). Māori horticulture was unfamiliar to the earliest European visitors to Aotearoa, restricting their understanding of what infrastructure may have been deployed, what crops were cultivated and what associated commensal plants were present.

Terrace features or ‘enclosures’ on the small islands of Manawatāwhi/Drie Koningen/Three Kings Islands (Figure 1) were observed by Abel Tasman and crew on the Heemskerck and Zeehaen in January 6th 1643, and regarded as possible cultivation systems:

‘On this land in various placed, and on the highest hills, were about thirty to thirty-five persons, men of tall stature, so far as they could see, with staves or clubs, who called to them in gruff, loud voices, which they could not understand. In walking they took great steps and strides… On this island they reckoned there would not be more people than had shown themselves, for on rowing round our people saw no dwellings, nor cultivated land except that near the freshwater. Here, on both sides of the waterfall, there were everywhere square enclosures after the manner of our country, green and pleasant. But what kind of vegetables they could not tell from the distance’ (Curnow and Beaglehole 1942 pp. 59–60).

If these square enclosures were māra, it is difficult to interpret what may have been cultivated, and why numerous (probable) whānau/families were occupying such a remote group of very small islands around 55 km northwest of Te Rerenga Wairua/Cape Reinga. It is also possible that these enclosures were not māra, instead being abandoned house platforms overgrown with vegetation. Regardless, the small ~4 km2 area of the largest island of Manawatāwhi, and the number of people observed suggests at least seasonal occupation, perhaps associated with ground-nesting sea-bird harvesting and fishing. Kūmara could have been planted as a perennial crop at any time of the year given the frost-free status of this northern locality. They could also have been planted at the end of ground nesting sea-bird harvests, which may have peaked from April to June, with root harvests occurring in subsequent seasons.

Figure 1. Cropped sketch of Manawatāwhi by Isaac Gilsemans from Valentyn (1725, Vol. 3 Part II: 52).

More detailed descriptions of Māori cultivation were later provided by the crew on James Cook’s voyages to Aotearoa between 1769 and 1773 (Salmond 1991; Leach 2005). The Endeavour crew were partly familiar with taro and kūmara cultivation practices based on their earlier visit to the Society Islands, French Polynesia. On October 9th 1769, the ship surgeon, William Monkhouse, on close observation of the expansive crop production systems of Anaura, Poverty Bay, wrote in his journal:

‘The ground is completely cleared of all weeds – the mold broke with as much care as that of our best gardens. The sweet potatoes [Ipomoea batatas] are set in distinct little molehills which are ranged in some in straight lines, in others in quincunx. In one Plott I observed these hillocks, at their base surrounded with dried grass [Poaceae grass species]. The Arum [Colocasia esculenta] is planted in little circular concaves, exactly in the manner our Gard’ners plant Melons as Mr – informs me. The Yams [Dioscorea cf. alata] are planted in like manner with the sweet potatoes; these Cultivated spots are enclosed with a perfectly close pailing of reeds [Cyperaceae and Juncaceae species] about twenty inches [50 cm] high. The Natives are now at work compleating these fences… The radical leaves or seed leaves of some of these plants are just above the ground. We therefore suppose their seed time to be about the beginning of this month. It is agreed that there are a hundred acres [40 hectares] of ground cultivated in this Bay – the soil is light and sandy in some parts – on the sides of the hills it is a black good mold. We saw some of their houses ornamented with gourd [Lagenaria siceraria] plants in flower. These with the Yams, sweet Potatoes and Arum are so far as we yet know, the whole of what they Cultivate… (Cook and Beaglehole 1968 pp. 583–584).

Also at Anaura, Sydney Parkinson, surgeon and artist on the Endeavour remarked that: ‘Adjoining to their houses are plantations of Koomarra and Taro: These grounds are cultivated with great care, and kept clean and neat.’ (Parkinson 1784 p. 97). Joseph Banks added some further details whist at Anaura, remarking on the early phase of the cultivation cycle:

‘Their plantations were now hardly finished but so well was the ground tilld that I have seldom seen even in the gardens of curious people land better broke down. In them were planted sweet potatoes [Ipomoea batatas], Cocos [Colocasia esculenta] and some one of the cucumber [probably Lagenaria siceraria] kind, as we judged from the seed leaves which just appeard above the ground; the first of these were planted in small hills, some rangd in rows other in quincunx all laid by a line most regularly, the Cocos were planted on flat land and not yet appeard above ground, the Cucumbers were in small hollows or dishes much as we do in England. These plantations were from 1 or 2 to 8 or 10 acres each, in the bay might be 150 or 200 acres in cultivation tho we did not see 100 people in all. Each distinct patch was fencd in generally with reeds placd close one by another so that scarcely a mouse could creep through’ (Beaglehole, 1963 2nd edition, I p. 417).

In 1769, the quincunx pattern of small hills or ‘molehills’ of probably imported ‘light and sandy’ soil described by the Endeavour crew, are common methods of cultivating root or tuberous vegetables throughout the Pacific Islands and elsewhere. Large scale archaeological excavations in the Waikato region have revealed equivalent crop production systems to those described by Monkhouse (Gumbley et al. 2003). These archaeological findings indicate that the term ‘garden’, meaning ‘a piece of ground adjoining a house, in which grass, flowers, and shrubs may be grown’ (Oxford English Dictionary, 2021) fails to capture the scale of Māori horticulture (Jones 2005). Indeed, Māori appear not to have an equivalent term for garden. Biggs indicates that kāri is a homonym or transliteration for ‘garden’ (Biggs 2012), as frequently used in early translations of the Old Testament, and ‘The garden of Eden’, for example. Māra, is now commonly used in te reo for garden, but was defined by Williams (1844) as ‘a cultivation’ and in later editions of the Williams dictionary as a ‘plot of ground under cultivation’, or ‘farm’.

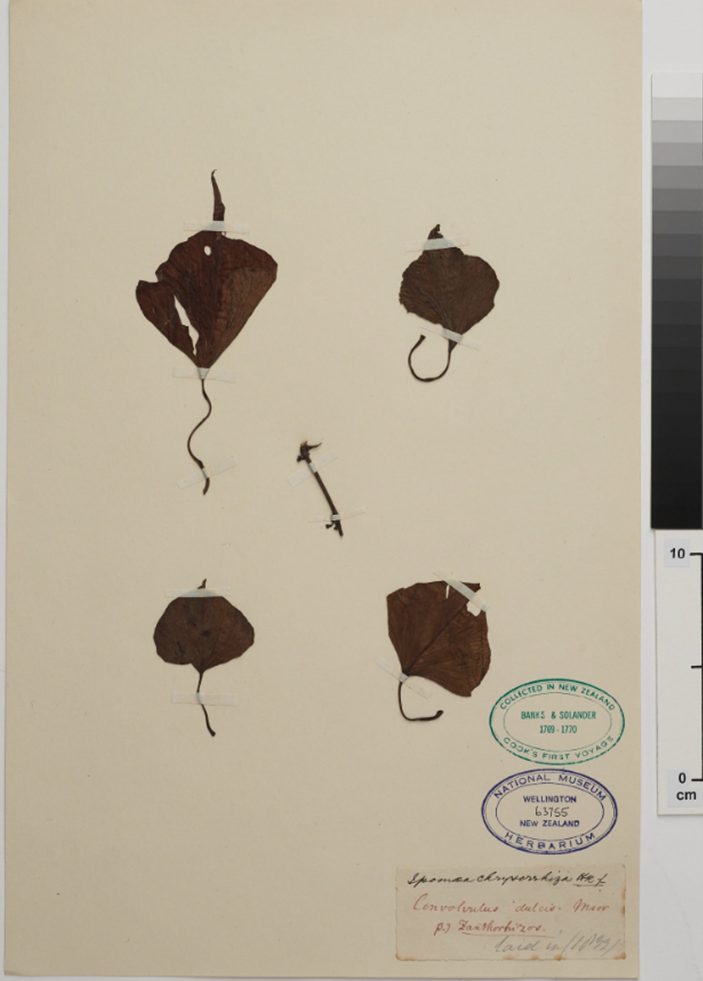

Other root or tuberous plants observed in 1769 and categorised as crops and not as ‘wild’ species by the Endeavour crew included yams. It is possible that some of the Māori varieties of kūmara were misidentified as uwhi/yams as they have slightly reniform immature leaves (Yen 1974) (Figure 2) similar to the yam Dioscorea alata. It is also unclear whether Tupaia (arioi/high priest from Ra’iatea), on board the Endeavour in 1769, assisted any of the crew with the plant identification, given the status of uwhi in his homeland, and the cultivation practices of this and other crops.

Figure 2. (left) Young leaves of a specimen of kūmara Ipomoea batatas collected by Banks and Solander in 1769, location uncertain; WELT 63755. Source: http://www.collections.tepapa.govt.nz.

(below) Mature leaves of kūmara, taputini variety grown in Ōtautahi/Christchurch, March 2020

Weeds

The Endeavour crew descriptions of ‘clean and neat’ cultivation systems, ‘completely cleared of all weeds’ indicated to Helen Leach (2005) that they may have been weed free. Here she follows the prevailing ideas of early botanists such as Cockayne (1928), and the ethnographer Elsdon Best (Best 1925), that Māori may not have been afflicted with horticultural weeds as they are ‘lacking’ in the indigenous flora of Aotearoa. In support of this contention, she presents the case that there is a lack of Polynesian cognate terms for weeds in te reo Māori. However, a number of terms for weeds, or places cleared of weeds, were recorded by Williams (1844), collated between 1826-1844. Such terms include ‘otaota – grass, weeds, rubbish’, and ‘hutinga – a place cleared from weeds preparatory for cultivation’. Other exceptions to this maybe pakihi and kokihi, terms used to describe places where fern root is dug and where weeds including Oxalis corniculta and O. exilis, also named kokihi, are prevalent. She also points out that by the 1840s weeds of European origin were widespread, and ‘perceived by Maori as a threat to the productivity of their lands’. Together, the ‘garden without weeds’ concept runs counter to what has been experienced by all traditional horticultural societies (Snir et al. 2015). Leach (2005) also presents the counter argument and more likely reading of these early accounts that the Anaura cultivations were in the earliest part of the seasonal production cycle of taro or kūmara, as suggested by Banks, and were thus ‘cleared of all weeds’.

More critical to the question of weeds were the observations of Cook and Johann Reinhold Forster returning to an area in Tōtaranui/Queen Charlotte Sound in 1777. In 1773, with a local rangatira Teiratu, planted five ‘gardens’ of potatoes and other European vegetables in Motuara (Hippa island) and Kokomohua (Long island). Forster described the state of these gardens as follows:

‘… at all the other gardens then planted by Captain Furneaux, although now wholly over-run with the weeds of the country, we found cabbages, onions, leeks, purslain, radishes, mustard, etc., and a few potatoes. These potatoes, which were first brought from the Cape of Good Hope, had been greatly improved by change of soil; and, with proper cultivation, would be superior to those produced in most other countries. Though the New Zealanders are fond of this root, it was evident that they had not taken the trouble to plant a single one (much less any other of the articles which we had introduced); and if it were not for the difficulty of clearing ground where potatoes had once been planted, there would not have been any now remaining.’ (Best 1925 pp. 149–50)

This raises the question, what ‘weeds of the country’ would have occupied these gardens left fallow for nearly four years?

Fallow vegetation

Leach (1984: 61; 2005: 271) suggests that: ‘the style of gardening practised on the hillside and adjacent flat land at Anaura Bay [observed by Cook and others] appears to have been a form of swiddening (slash and burn horticulture), in which secondary forest or scrub, which had grown up on old cultivation sites, was burnt after a long fallow period, perhaps 14–25 years or longer, thereby releasing its nutrients for a short period of root crop production’. Furthermore, it is unlikely that Cook and crew, nor the naturalists on the Endeavour were entirely aware of the ecology of long-fallowed areas, or to whether they were looking at ‘wild’ or previously cultivated areas (although see quote from William Anderson below regarding wild celery). Of the māra observed by Banks and Solander in 1769, not all of them were necessarily built on hill slopes, with some occupying the margins of wetlands. Here, cultivation cycles may have required shorter fallow times, especially if the soils were regularly flushed with nutrients from the associated streams. Such variation in cultivation practices, and soils, likely reflected the diversity of target crops, and undoubtedly resulted in differing assemblages of commensal species, along with weeds, but especially plants adapted to frequent burning including ground ferns (e.g. aruhe Pteridium esculenta), the fireweed toatoa Haloragis erecta, and tutu Coriaria arborea.

Te Whanganui-o-Hei Mercury Bay and Ipipiri eastern Bay of Islands

During the Endeavour visit to Poverty Bay in October 1769, Banks and Daniel Solander, and field hands, collected ‘… not above 40 species of Plants in our boxes, which is not to be wonderd at as we were so little ashore and always upon the same spot; the only time we wanderd about a mile from the boats was upon a swamp where not more than 3 species of Plants were found.’ (Banks 1962a p. 406). They made further herbarium collections in other northern North Island locations, including in Te Whanganui-o-Hei (at Wharekaho and Purangi) on the Coromandel Peninsula, and on the islands of Ipipiri (at Moturua and Motuarohia). These are later two areas are pivotal to our understanding of Māori horticultural practices in 1769, at least for the coastal lowlands and small offshore islands of northern Aotearoa, principally a result of recent archaeological research at Ahuahu (Prebble et al. 2019) and Moturua, discussed later.

Figure 3. Area of pasture grass, where the Endeavour crew landed at Wharekaho Bay, below Wharetaewa Pā, near Whitianga, Mercury Bay. The lands surface still holds evidence of former cultivation.

[1]Approximately 541, 545 and 91 herbarium duplicate specimens of Banks and Solander’s collections from New Zealand during the Endeavour voyage of 1769-1770, are held in the herbaria of Te Papa (WELT), Auckland Museum (AK), and Manaaki Whenua Landcare Research (CHR), respectively (Brownsey 2012). Images of most of these duplicates are available online along with the Bank’s Florilegium, a series of copperplate engravings of botanical specimens from the water colour paintings of Sydney Parkinson (http://www.collections.tepapa.govt.nz, https://www.aucklandmuseum.com/collections-research). See appendix for examples.

At Te Whanganui-o-Hei, including at Wharekaho Bay, Banks noted some more species cultivated by Māori and other plant use practices:

‘… such a party of Indians were there consisting of 40 or 50… Their food, in the use of which the[y] seem to be moderate, consists of Dogs, Birds, especialy sea fowl as penguins albatrosses &c, fish, sweet potatoes, Yams, Coccos [Colocasia esculenta], some few wild plants as sow thistles [Sonchus kirkii or S. asper], Palm Cabbage [ti Cordyline australis and or nikau Rhopalostylis sapida] &c. but Above all and which seems to be to them what bread is to us, the roots of a species of Fern very common upon the hills and which very nearly resembles that which grows on our hilly commons in England and is calld indifferently Fern, Bracken, or Brakes [Pteridium esculentum]’ (Banks 1962b p. 19)

Contrary to the observations of Monkhouse at Anaura, the Māori cultivations at Wharekaho were not cleared of all ‘weeds’, but retained ‘some few wild plants’ including sow thistles (Sonchus sp., see below). It is also likely that Wharekaho was one of the locations where a specimen of immature kūmara leaves (Figure 2) was collected by Banks and Solander, now housed within the Te Papa Herbarium, along with over five hundred other specimens of different species[1]. Of these collections, the majority are from herbs and other plants that may have been common or even abundant on cultivated or fallow areas.

When Cook visited Moturua, a 150 ha island at Ipipiri, he wrote:

‘this Island is about 3 Miles in circuit and hath upon it 40 or 50 Acres [16-20ha or ~10-15% of land area] of land cultivated and planted with roots. This Island as well as most others in this Bay seems to be well Inhabited. Sent the Long boat to the above Id for water and some hands to cut grass’ (Cook and Beaglehole 1968).

Again, Cook was probably describing active kūmara cultivations in the early part of the production cycle, and not areas under fallow vegetation which may have made up a large proportion of the land area of the island.

Along with plant collecting, as well as the exchange of Māori tāonga/material culture items, Te Whanganui-o-Hei and Ipipiri were likely the first locations to receive rīwai or taewa/potato Solanum tuberosum and other vegetables (Harris, 2002). Cook exchanged potatoes in 1769 with a rangatira at Wharekaho (Best 1925 p. 282), and presumably exchanged potatoes during his visit to Ipipiri. Prior to his death at Te Hue in 1772, Marion Du Fresne also established a vegetable garden with potatoes on Moturua (McNab 1914 p. 399). The close similarities and familiarity of the white and blue flowers of potato with the three different species of poroporo or poro Solanum indigenous to Aotearoa (S. americanum, S. aviculare, and S. laciniatum), may have contributed to its rapid deployment by Māori (Roskruge 2012). Counter to some claims, it is unlikely that potato was introduced prior to European arrival, given that it can be grown in abundance in Murihiku Southland, but was not deployed there until the early 19th century. In addition the recent fossil analyses of buried cultivated soils from Ahuahu (including from Moturua, see below), revealed abundant seeds of all of the above Solanum species, but not of potato (Prebble et al. 2019). This aside, the use of potato by Māori, especially in Ipipiri, allowed for traditional cultivation practices, that closely followed kūmara cultivation, to continue in the new colonial economy. Potato production was dominated by Māori in many parts of Aoteroa up until around the 1850s, with key areas for production built in Ipipiri including at Motorua (see below).

[1]Approximately 541, 545 and 91 herbarium duplicate specimens of Banks and Solander’s collections from New Zealand during the Endeavour voyage of 1769-1770, are held in the herbaria of Te Papa (WELT), Auckland Museum (AK), and Manaaki Whenua Landcare Research (CHR), respectively (Brownsey 2012). Images of most of these duplicates are available online along with the Bank’s Florilegium, a series of copperplate engravings of botanical specimens from the water colour paintings of Sydney Parkinson (http://www.collections.tepapa.govt.nz, https://www.aucklandmuseum.com/collections-research). See appendix for examples.

Figure 4. Ōtūpoho Bay, Moturua, Bay of Islands. Currently jointly managed by Ngāti Kuta Patukeha with the Department of Conservation. Like at Wharekaho, surface archaeological features are common throughout the bay including stone-lined terraces and drains.

Fossil records of korare leafy green vegetables

Wetlands, especially swamps associated with archaeological contexts, provide the best preservation conditions for fossil evidence of commensal plants. Notable wetlands include the Te Kohika swamp pā, in the Ngāti Awa rohe, near the Tarawera River, on the central Rangitaiki floodplain in the Bay of Plenty (Lawlor 1979; Horrocks et al. 2003; Irwin 2004; McGlone and Jones 2004); and the more recent studies of wetlands on the offshore islands at Ahuahu (McIvor and Ladefoged 2016; Holdaway et al. 2019; Prebble et al. 2019) in the rohe of Ngāti Hei; and Moturua (see below) in the rohe of Ngāti Kuta Patu Keha (Peters 1975; Robinson et al. 2019). From these few sites, we can establish the key characteristics of wetlands that may make them conducive for good fossil preservation of seeds and pollen.

The offshore islands are low lying, and have small coastal wetlands impounded or built up behind small sand dunes or boulder beaches. The hydrology of these wetlands can be characterised as low energy, whereby floods occur less frequently by nature of the small size of the river or stream catchments. These geographical characteristics, along with the often frost-free status of most of the northern offshore islands, also make them ideal targets for Māori cultivators. It has also been argued that the offshore islands are also more similar in scale to the homeland islands of ancestral Hawaiki, than mainland Aotearoa (Prebble et al. 2019). Earlier research on Ahuahu, led me to approach a team of archaeologists and manawhenua running excavations at Mangahawea on Moturua about the prospect of locating buried wetland sediments on the islands.

The main question posed of Moturua was whether comparable evidence of wetland cultivation found on Ahuahu be obtained for other offshore islands? Is there a comparable pattern to taro, kūmara and korare cultivation on Moturua prior to Pākehā arrival? In addition, can the fossil evidence that small wetlands provide, enable more recent periods of Māori landuse since 1769 to be characterised, placing more recent tribal and family histories in context of continuing traditions of cultivation? Can fossil evidence support the recent archaeological findings of what are thought to be infrastructure for potato cultivation by Māori in the 19th century? Māori dominated potato production and with it the economy of the early colonial period, with some historians arguing that the musket wars might more aptly be called the ‘potato wars’ (Ballara 2003).

Figure 5. A sediment core (top left) taken between a depth of 100-150 cm below the wetland surface at Ōtūpoho Bay. This section has been radiocarbon dated to between 1500 to 1850 AD. The first appearance of numerous seeds of the milk weed Euphorbia peplus (top middle, 2 mm in diameter) and pollen of Pinus pine tree (top right, 0.1 mm in diameter) identified in the upper sediments of the wetland are used to date the periods from 1865 and 1950 AD, respectively. Regular botanical collections that began with Banks and Solander in 1769, allow for the precise determination of when many invasive species, including these species, were first recorded as naturalised (naturally spreading) throughout Aotearoa.

Ōtūpoho

Ōtūpoho Bay is situated on the east side of Moturua. A series of small (<0.1 ha, at 10 m

asl) mires lie 150-200 m inland, up a small seasonally active stream catchment (<10 ha).

Remnant terraces, stone alignements, and house platforms are found along the periphery and immediately above the mires on the hillslopes (Peters 1975). One of the mires hold around organic-rich sediments overlying compacted alluvial clays and sands. In December 2019, sediment cores (Figure 5) were taken down to 2 m in depth and a 1 x 1m excavation were conducted in order to retrieve sediments for seed and pollen analysis, with some of the initial results presented in Figure 6, and summarised in Table 1.

Figure 6. Stratigraphic diagram summarising the main types of vegetation represented from the pollen & spore, and seed analysis (left silouhette diagrams. Also presented are the percentages of the main tree and shrub (dark green), dryland herb & korare leafy green vegetables (orange), wetland herb (blue), fern (light green) and exotic plant (red) pollen and spores (small closed/shaded bars and triangles) and macrobotanical remains (large open bars and triangles) recorded from Ōtūpoho core and pit excavation (EA1). Taxa are arranged according to depth and radiocarbon chronology and exotic seed introduction times (left column). The triangles represent data points with <5% of the total sum. Taxa in purple are regarded as either extirpated or extinct. Pollen & spore and seed concentration data are also presented. The left most column indicates the presence of taro Colocasia esculenta pollen in the record (red circles). The five interpretation zones (right column) are based on the main changes in the fossil dataset.

Table 1. Summary of pollen, spore and seed record from Ōtūpoho (EA1)

Zone; Depth (cm); Ages | Pollen & spores | Seeds | Interpretation |

A; 200-170cm; older than AD 1400 | Poor preservation | Poor preservation | Early occupation |

B; 170-140 cm; AD 1400- 1550 | Pteridium spores are high in this zone. Charcoal particles were recorded in low concentrations. Low proportions of herbs. | Coriaria arborea seeds and charred Pteridium pinnues dominate indicative of fallow vegetation and frequent fires | Fallow vegetation indicative of sustained clearance for crop production, and perennial low intensity cultivation |

C; 140-110 cm; AD 1550 to ~1810 | Pteridium spores recorded in highest proportion, indicative of very little forest cover. | Highest proportions of korare represented, noting that only celery, watercress and sow thistle species are show (see Appendix). Marked increase in dryland & wetland herbs, (but less Coriaria) indicative of different fallow regime including the blocking of drainage to manage water flows | High intensity cultivation of taro, kūmara, and leafy green vegetables |

D; 110-80 cm; after AD 1810-1875 | Increase in dryland & wetland herbs associated with increased charcoal particles | Further increase in wetland herbs, and rapid influx of exotic weeds | Exotic weeds (annuals), less fallow vegetation, possibly indicative of high intensity potato cultivation which could be grown throughout the year over multiple seasons |

E; 80-50cm; AD 1875-1920 | As above, but with increase in wetland herbs | Taro pollen recorded for the first time. Increase in dryland herbs, and charred Pteridium pinnules. | Perennial, low intensity cultivation including taro, and probably kūmara & potato |

F; 50-0 cm; AD 1920-present | Rapid increase in dryland (especially grasses) and wetland herbs. Lowest proportions of ferns recorded. | Dominance of wetland herbs probably resulting from the infilling of drainage channels and streams with eroded sediments | Conversion to pastoral grass, then return to manuka and pōhutukawa forest |

The fossil evidence from Ōtūpoho, thus far, show that between 1300-1500 AD, although no specific fossil evidence of taro and kūmara have been identified, the vegetation was dominated by dryland shrub species especially tutu, characteristic of fallow cultivation. Between 1500-1800 AD, both Moturua and Ahuahu reveal high intensity cultivation, which likely included taro and kumara, but also korare. Some of the korare represented in the fossil record, including Sonchus kirkii and Rorippa palustris, are either annual or biennial herbs that would have flourished under repeated burning in a highly used cultivation system (Prebble et al. 2019).

By 1769, fallow vegetation on Moturua including aruhe were very abundant, with Cook’s observations of up to 20ha of active cultivations, further suggesting that fallow areas likely covered much of the island. After 1800, fallow vegetation (aruhe and tutu) expanded further, and it may have been that potato cultivation was concentrated in the lowland valley flats that were holding larger areas of wetlands at that time. The enhanced water holding capacity of the small valleys may have been critical to sustain potato production for the rapidly growing colonial economy. By 1827, J.S. Dumont D’Urville, on visiting the abandoned hospital and garden site of Marion du Fresne found after: ‘only gathering a few plants here and there, for its vegetation is neither varied nor flourishing and consists for the most part of bracken and brushwood, neither of them at all remarkable’ (Beever et al. 1984). However, he never commented on the extent of potato cultivation, which may have been focused on other parts of the island. The abundance of exotic annual weeds and charred materials, especially after 1840, does strongly point to substantial land-use, including repeated burning.

Although the sediment dating measures employed here are not absolute (Figure 5), it seems that by 1875, crop production, including taro, had shifted towards perennial or low intensity cultivation. This may reflect a cultivation strategy of a small kāinga, not of high intensity production intended for the expanding colonial market. After 1920, most of the tree and shrub vegetation was cleared and converted to pastoral grassland for stock animals. Stock were removed by 1976, but at that time only a few areas, including Ōtūpoho Bay, had been kept clear of mānuka Leptospermum scoparium, kānuka Kunzea ericoides and exotic trees and shrubs (Beever et al. 1984).

Conclusions

The celery, cress and sow thistle species of korare touched on here (and explored further in the appendix), based on the early collections and surveys of botanists, as well as the fossil records from Moturua and Ahuahu, were formely abundant across Aotearoa prior to European colonization. Some of these species have been interbred (hybridised) or displaced by more competitive introduced species since European colonisation, with Sonchus oleraceus as a primary example. The loss of kurī Māori followed a similar historical trajectory. When Cook and the Endeavour crew first observed Māori cultivations in 1769 it is clear that the sites they visited had undergone substantial ecological changes in the previous centuries. They also clearly misread many parts of the landscape as wild, particularly areas kept in fallow from repeated burning, colonised with dense ground ferns and shrubs such as tutu. These observations have perpetuated a series of poorly founded claims in historical treatments of Māori cultivation. These claims purport that the scale and diversity of cultivation systems was low, and weeds, did not impact production, unlike all other traditional horticultural societies.

As someone of Southern Māori descent (Kāti Irakehu ki Wairewa), I grew up with the contradictory portrayals of our tīpuna as hunter-gatherers, where the horticultural roster of introduced crops grown in the North was limited to kūmara (Ipomoea batatas) as far south as Horomaka Banks Peninsula. Our tīpuna are thought to have relied more heavily on pounded and cooked aruhe, and other wild mahinga kai vegetables for our carbohydrate sources. These portrayals were perpetuated by hypotheses biased by evidence that suggested that hunting, particularly of moa, and fishing (shell-fishing), formed almost the entire basis of the early Māori economy. In no way was horticulture important, let alone the potential for extensive trade of the rich coastal resources of Te Wai Pounamu, with the larger scale horticultural production of the North. Up until recently archaeologists have stuck to the notion that horticulture at scale only appeared later in what was termed the ‘Classic’ period, characterised by pā and large kāinga and evidence for horticulture, albeit mostly in the North. This maybe the case, but based on the diversity of plants with economic potential recorded in fossil records soon after initial Māori arrival, the process of crop adaptation began at the onset. This was also likely the case in Te Wai Pounami with the development new domesticated crops such as karaka (Corynocarpus laevigatus), again only as far south as Horomaka, and tī kouka/kāuru (Cordyline australis) pith even further south.

As many archaeologists (Gumbley et al. 2003; Furey 2006; McIvor and Ladefoged 2016) have suggested, we need to re-think our view of traditional Māori cultivation practices across Aotearoa. The evidence presented here shows that we have several powerful tools at our disposal to understand the past. The diversity of korare identified in the fossil archives found in buried sediments in wetlands unequivocally shows that cultivation practices were highly diverse, and that we should not narrow our focus to just taro or kūmara.

The research presented here also acts as a call to better envisage these ancestral species and ecosystems, and begin to forge different learnings, potentially by way of establishing experimental cultural ecosystems, particularly different types of cultivations or mahinga kai areas. We should all be able experience the cuisine of the ancestors, but also understand the complexity of centuries of adapting cultivation practices to the often hostile environments of Aotearoa.

Kā mihi/Acknowledgements

Ko te kaupapa nei, kei raro te maru o Ngāti Hei, ā, Ngāti Kuta, Patukeha hoki. Ki ngā kaumātua e rua ko Joe Davis (ONZM) rāua ko Matutaera Clendon (ONZM), ka nui te mihi mahana ki aua tōtaranui o te ao Māori, mō rāua tautoko, manaaki ā aroha mō tēnei rangahau pūtaiao. Muramura ahi kā ki uta, muramura ahi kā ki tai.

Special thanks to James Robinson, Jack Kemp, Tom Barker and Andrew Blanchard for their assistance with our research at Ōtūpoho Bay on Moturua. To my colleagues working on the long-standing collaborative project on Ahuahu, including Thegn Ladefoged, Simon Holdaway, Alex Jorgensen, Rebecca Phillips, Rod Wallace, Josh Emmitt, and Louise Furey, with support from the Fay and Richwhite families, kā mihi nui. I would also like to acknowledge staff of the herbarium at the Auckland Museum.

References

Anderson A. 2009. The rat and the octopus: initial human colonization and the prehistoric introduction of domestic animals to Remote Oceania. Biological Invasions 11: 1503–1519.

Ballara A. 2003. Taua: “musket wars”, “land wars” or tikanga? : warfare in Māori society in the early nineteenth century. Auckland: Penguin Books.

Banks J. 1962a. The Endeavour Journal of Joseph Banks 1768-1771 Volume 1 (JC Beaglehole, Ed.). Sydney: Angus and Robertson.

Banks J. 1962b. The Endeavour Journal of Joseph Banks 1768-1771 Volume 2 (JC Beaglehole, Ed.). Sydney: Angus and Robertson.

Beever RE, Esler AE, Wright AE. 1984. Botany of the large island of the eastern Bay of Islands, Northern New Zealand. Tane 30: 251–273.

Best E. 1925. Maori agriculture. Wellington: Board of Maori Ethnological Research, Dominion Museum.

Biggs B. 2012. English–Maori, Maori–English Dictionary. Auckland, UNITED STATES: Auckland University Press.

Brownsey PJ. 2012. The Banks and Solander collections—a benchmark for understanding the New Zealand flora. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand 42: 131–137.

Clark G, Petchey F, Hawkins S, Reepmeyer C, Smith I, Masse WB. 2013. Distribution and extirpation of pigs in Pacific Islands: a case study from Palau. Archaeology in Oceania 48: 141–153.

Cook J, Beaglehole JC. 1968. The voyage of the Endeavour, 1768-1771, Volume I. Cambridge [England: Published for the Hakluyt Society at the University Press.

Curnow A, Beaglehole JC (Eds.). 1942. Abel Janszoon Tasman and the discovery of New Zealand (MF Vigeveno, Tran.). Wellington [N.Z.]: New Zealand Government, Department of Internal Affairs.

Furey L. 2006. Māori gardening: an archaeological perspective. Wellington: Department of Conservation, New Zealand Government.

Gumbley W, Higham T, Lowe D. 2003. Prehistoric horticultural adaptation of soils in the Middle Waikato Basin: review and evidence from S14/201 and S14/185, Hamilton. New Zealand Journal of Archaeology 25: 5–30.

Harris, G. 2002. Ngā rīwai Māori: the perpetuation of relict potato cultivars within Māori communities in New Zealand In: Yoshida S, Matthews PJ, eds. Vegeculture in Eastern Asia and Oceania. Osaka: The Japan Center for Area Studies, National Museum of Ethnology, 303–317.

Holdaway SJ, Emmitt J, Furey L, et al. 2019. Māori settlement of New Zealand: The Anthropocene as a process. Archaeology in Oceania 54: 17–34.

Horrocks M, Irwin GJ, McGlone MS, Nichol SL, Williams LJ. 2003. Pollen, Phytoliths and Diatoms in Prehistoric Coprolites from Kohika, Bay of Plenty, New Zealand. Journal of Archaeological Science 30: 13–20.

Irwin G. 2004. Kohika: The Archaeology of a Late Māori Lake Village in the Ngāti Awa Rohe, Bay of Plenty, New Zealand. Auckland University Press.

Jones G. 2005. Garden Cultivation of Staple Crops and Its Implications for Settlement Location and Continuity. World Archaeology 37: 164–176.

Lawlor I. 1979. Palaeoenvironment analysis: an appraisal of the prehistoric environment of the Kohika Swamp Pa (N681104), Bay of Plenty.

Leach H. 1984. 1,000 Years of Gardening in New Zealand. Reed.

Leach H. 2005. Gardens without weeds? Pre-European Maori gardens and inadvertent introductions. New Zealand Journal of Botany 43: 271–284.

McGlone MS, Jones KL. 2004. The impact of Polynesian settlement on the vegetation of the coastal Bay of Plenty In: Kohika: The Archaeology of a Late Māori Lake Village in the Ngāti Awa Rohe, Bay of Plenty, New Zealand. Auckland: Auckland University Press, 20–44.

McIvor IH, Ladefoged TN. 2016. A multi-scalar analysis of Māori land use on Ahuahu (Great Mercury Island), New Zealand. Archaeology in Oceania 51: 45–61.

McNab R. 1914. Historical records of New Zealand. Wellington: New Zealand Government Printer.

Parkinson S. 1784. A Journal of a Voyage to the South Seas. London: George-Yard, Lombard-Street.

Peters KM. 1975. Agricultural gardens on Moturua Island in the Bay of lslands. New Zealand Archaeological Association Newsletter 23: 171–180.

Prebble M, Anderson AJ, Augustinus P, et al. 2019. Early tropical crop production in marginal subtropical and temperate Polynesia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences: 201821732.

Robinson J, Blanchard A, Clendon MTN, Maxwell J, Sutton N, Walter R. 2019. Mangahawea Bay Revisited: a reconsideration of the stratigraphy and chronology of site Q05/682. Journal of Pacific Archaeology 10: 45–55.

Roskruge N. 2012. Tahua-Roa: Food for your visitors; Korare: Māori green vegetables, their history and tips on their use. Palmerston North: Institute of Natural Resources, Massey University.

Salmond A. 1991. Two Worlds: First Meetings Between Maori and Europeans, 1642-1772. University of Hawaii Press.

Snir A, Nadel D, Groman-Yaroslavski I, et al. 2015. The Origin of Cultivation and Proto-Weeds, Long Before Neolithic Farming. PLOS ONE 10: e0131422.

Wood JR, Herrera MJB, Scofield RP, Wilmshurst JM. 2016. Origin and timing of New Zealand’s earliest domestic chickens: Polynesian commensals or European introductions? Royal Society Open Science 3.

Yen DE. 1974. The sweet potato and Oceania: an essay in ethnobotany. Honolulu: Bishop Museum Press.

Appendix

Scurvy grass and leafy green vegetables

In the 17th and 18th centuries, scurvy presented more of risk to the health of European crews on long-distance voyages than most other afflictions. Ensuring the adequate consumption of fresh green vegetables to avoid scurvy, particularly of species in the Apiaceae and Brassicaceae families, by 1769, was widely recognised, most famously by Cook (Kodicek et al., 1969). Ngā tūpuna undoubtedly recognised the value of green vegetables for this same reason, and this may provide one explanation for the putative introduction of a number plants to different parts of Aotearoa, or introduced from the tropical Pacific Islands on ocean voyages. Because of their remedial value, the naturalists on board the Endeavour focused their collections on these plant families. In Aotearoa, there has been some debate as to what plants from these collections were referred to as scurvy grass (Lange and Norton, 1996), and whether these were retrieved from māra or from ‘wild’ contexts (Leach, 2005; Prebble et al., 2019). The first reference to these plants was made by Cook, on the 27th October 1769 at Ūawa, referencing: ‘…the north point of the Bay [‘Passage Point’] where I got as much Sellery and Scurvy grass as loaded the Boat’ (Cook and Beaglehole, 1968, p. 184). Banks later reflected on the availability of anti-ascorbic plants in Aotearoa: ‘Eatable Vegetables there are very few. We indeed as people who had been long at sea found great benefit in the article of health by eating plentifully of wild Celery, and a kind of Cresses which grew every where abundanly near the sea side.’ (Beaglehole 1962b: 8).

Celery

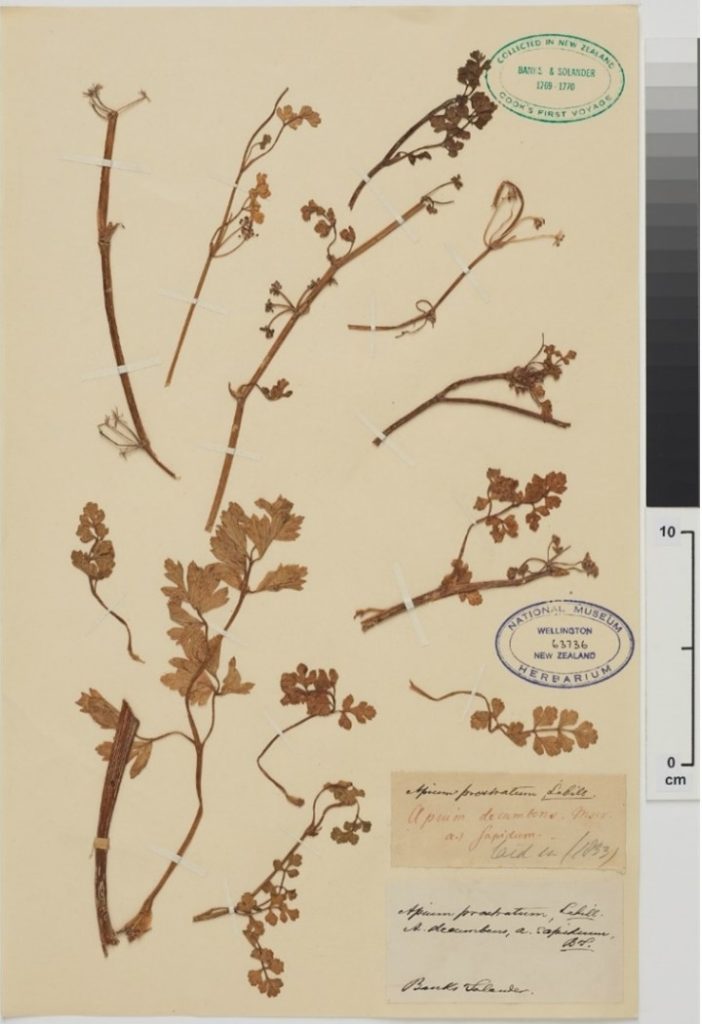

Also at Ūawa, Banks observed ‘a large supply of Celary, with which this countrey abounds…’, then in Ipipiri the Endeavour had ‘all hands emplyd in gathering Cellery which was here very plentiful’ (Banks, 1962). Beaglehole (1962), an editor of both the Endeavour journals of Cook and Banks, suggests that ‘sellery’, occasionally referred to by Banks as Apium antescorbuticum (now A. prostratum subsp. prostratum var. filiforme (A.Rich.) Kirk; SP063736 see Figure 1 (Webb et al. 1988; http://www.nzpcn.org.nz) which was regarded as being found across Aotearoa, ‘Novae Zelandiae, ubique’. The frequent reference to ‘wild celery’ does suggest that these were not procured from māra, however, William Anderson, the surgeon’s mate on the Endeavour, observed that it ‘grows plentifully almost in every cove, especially if the natives have ever resided there before…’ (Beaglehole, 1976, pp. 803–805). On later voyages, Cook and crew recorded the presence of ‘wild’ celery across Polynesia. In 1773, Georg Forster, referring to it as A. graveolens, the common European celery, noted that it was: ‘Abundant in New Zealand shores; moreover, we observed it in Easter Island [Rapa Nui], which importantly shows it is not confined to the tropical islands, and is of unknown provenance, the inhabitants as far as I know, and the sailors found it very tasty, and most of all for the salvation of scorbic acid.’ There are currently two species of indigenous Apium species recorded on Rapa Nui including A. australe Thouars and A. prostratum, which is also found in Aotearoa. Called tūtae kōau in te reo Māori (Solander recorded three names: tutagavai, tutaguaya, he tutaiga), A. prostratum is an almost strictly coastal herb, and is very similar to A. graveolens, as initially proposed by Forster, having highly variable leaf morphology, and distinct mericarps (fruits) (Webb et al. 1988; http://www.nzpcn.org.nz).

The Apiaceae/Umbelliferae plant family, including the common celery genus Apium, is comprised of several taxa that may have leaves or taproots that are palatable or have medicinal qualities, including for anti-ascorbic effect. Based on the collections of plants made by Banks and Solander that included ~350 species predominantly from the coastal lowlands of Aotearoa, a number of these are from the Apiaceae, including: A. prostratum, Centella asiatica, Hydrocotyle (x 4 species) and Scandia rosifolia (Hook.) J.W. Dawson (syn. Angelica rosifolia, Ligusticum aromaticum). Aside from their anti-ascorbic qualities, most of these plants were likely to have been collected by Banks and Solander because they were widely known in Europe. The shared geography and distribution of species was prominent interest for naturalists in formulating Enlightenment theories of the origin of life. Numerous specimens of the Hydrocotyle genus were collected, perhaps reflecting their abundance in the landscape and the diversity of habitats that each species occupied, and their highly polymorphic characteristics (Allan, 1961). However, it is also probable that Hydrocotyle species were prevalent in both active and fallow māra.

Figure 1a. Stems, leaves and inflorescence of a specimen of tūtae kōau Apium prostratum subsp. prostratum collected by Banks and Solander in 1769, location uncertain. Image source: http://www.collections.tepapa.govt.nz

1b Seeds or pollen (above image) of indigenous Apium have been rarely recorded in fossil deposits, and has not been recorded from Ahuahu or Moturua, but is found in the modern flora of both islands, growing on coastal rocky locations. Image source; https://apsa.anu.edu.au/

Centella uniflora is an endemic creeping herb and closely related to C. asiatica, found throughout the tropics, but assumed to have been introduced to much of Polynesia (Whistler, 2009). C. asiatica is widely known from India to Fiji as having medicinal properties particularly for the treatment of dysentery, and in Southeast Asia, the leaves are often eaten in salads (Burkhill, 1935). Few references point to its use by Māori, but given its prevalence in the diet of Austronesian language speakers, it is likely that Centella was used for medicine and food along with the closely related Hydrocotyle species. In Indonesia, C. asiatica has been used in plantations as a quick growing ground cover to prevent soil erosion. The indigenous celeries of Aotearoa may well have served a similar purpose in Māori crop cultivation.

Scandia rosifolia is an endemic aromatic semi-climbing herb, which can resprout vegetatively from basal stems. William Colenso described how Māori used the leaves of S. rosifolia as a diuretic, and a remedy for other diseases (Colenso, 1869). Banks and Solander recorded the te reo names koerie, koarik, koaligh [koariki] from a Māori informant. They also described it growing ‘on forest margins and in meadows’. According to Peter de Lange ‘The leathery leaves are rather strongly flavoured but make an interested addition to a summer salad if eaten before they are fully mature’ (http://www.nzpcn.org.nz). This endemic celery, similar to many of the indigenous leafy green herbs discussed here, is now regarded as a critical threatened species in Aotearoa (http://www.nzpcn.org.nz). It is now mostly found on isolated cliff faces on lowland and coastal sites north of the Ruahine Ranges, and the northern offshore islands. Its distribution was clearly much more extensive in 1769, and it is possible that Banks and Solander collected specimens from active or fallow māra.

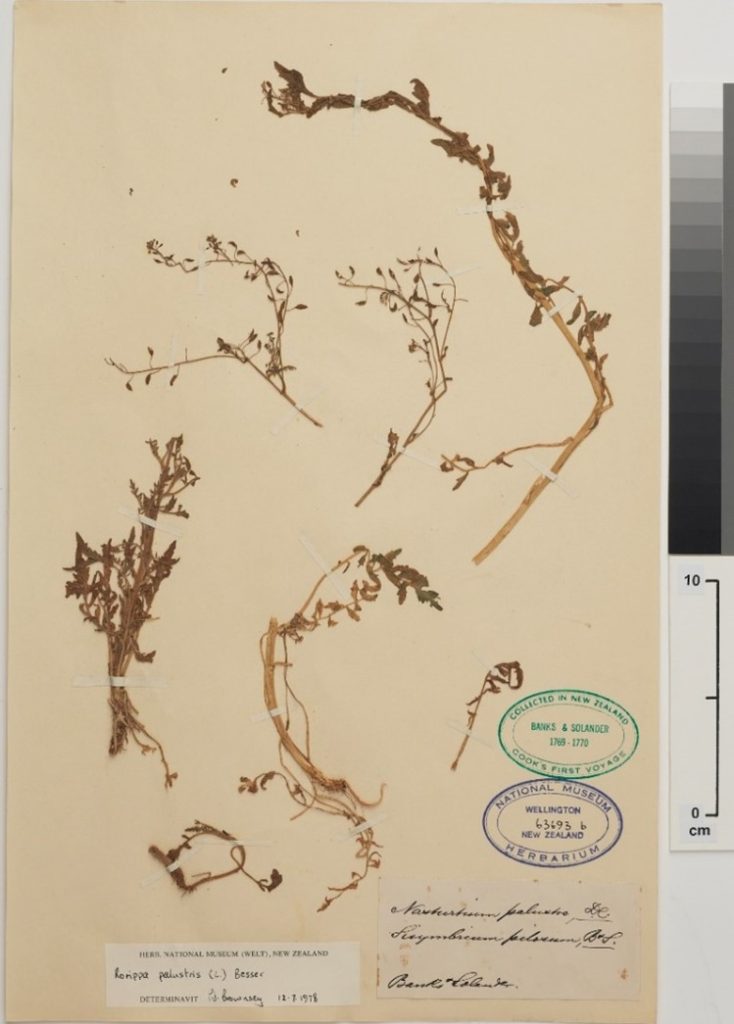

Scurvy grasses

Cresses, in the Brassicaceae family, make up most of what were regarded as scurvy grasses by the Endeavour crew (Lange and Norton, 1996). Beaglehole suggests that ‘Probably what Cook called scurvy-grass, Lepidium oleraceum; other candidates would be a wild cress called Poniu, Nasturtium palustre [Rorippa palustris] and Cardamine glacialis’ (Banks, 1962, p. 8). These may have been moreoften located by Banks and Solander in māra than ‘wild’ locations. They collected fruiting specimens of Rorippa palustris (SP063693/A-B, Figure 2; the name derived from the Latin palus or ‘swamp’) and the endemic cress Rorippa divaricata, which was described as Cardamine stylosa ‘in graminosis et locis ruderalis prope Tolaga, Opuragi, Totara Nui’ or ‘in grasslands and waste places at Tolaga, Opuragi and Totara Nui’ (Solander and Banks 1768-1771; SP063694/A-B (Figure 3), SP078887). ‘Waste places’ refer to areas overrun with weeds which may have formerly been cultivated, or in the context of R. divaricata or R. palustris, these may have been swampy areas, or drainage ditches. Lange and Norton (1996) conclude that R. divaricata probably constituted one of a number of cress species (Brassicaceae) under the vernacular ‘scurvy grass’, a term later restricted to Lepdium oleraceum.

Figure 2. (left) Stems, leaves and fruits of a specimen of poniu Rorippa palustris collected by Banks and Solander in 1769, location uncertain. Image source: http://www.collections.tepapa.govt.nz

(bottom left) Scanning electron micrograph of fossil R. palustris seed (whole) from Tamewhera, Ahuahu radiocarbon dated to ~1500 AD; 0.5mm diameter

(bottom right) Scanning electron micrographs of the distinctive colliculate surface of fossil R. palustris seed from Tamewhera, Ahuahu radiocarbon dated to ~1500 AD; 0.1mm diameter

1b Seeds or pollen (above image) of indigenous Apium have been rarely recorded in fossil deposits, and has not been recorded from Ahuahu or Moturua, but is found in the modern flora of both islands, growing on coastal rocky locations. Image source; https://apsa.anu.edu.au/

The Endeavour crew were not the only Europeans to seek out celery and scurvy grass in 1769. In the Hokianga, in December of that year, Jean François Marie de Surville, captain of the St Jean Baptiste in exchange for kūmara and what appeared to be two species of watercress (probably Rorippa or Cardamine spp.) and celery (probably A. prostratum), gave a rangatira chief a number of pigs, a rooster and hen, wheat, rice, and peas (Dunmore, 1981; Salmond, 1991). Sixty crew of the St Jean Baptiste had already died of scurvy on route to Aotearoa, and the desperate need for fresh food supplies likely provoked a hostile exchange. Through hand signals de Surville tried to explain how to sow, harvest, mill, and cook wheat. Aside from this exchange of vegetable products, the fact that watercress and the celery were exchange items indicate that these plants may have been abundant in the wild or were more likely cultivated, including in wetlands. Tragically, Ranginui, a rangatira, was taken hostage on the St Jean Baptiste after the above exchange, captured during an altercation and destruction of his kainga, died of scurvy on the voyager to South America (Dunmore, 1981).

A central problem to understanding the cultural status of many korare, including both Rorippa species is that they are highly polymorphic (presenting different plant morphologies under differing environmental conditions). Such traits include variable branching, leaf size, annual or short-lived life histories, high seed/propagule production and dispersibility, and the capacity for clonal reproduction, each allowing plants to adapt to frequently disturbed habitats affected by human activity, such as cultivation systems. Hence, many of these plants have been described as weeds. These polymorphic traits have consequently led to ongoing differing taxonomic (scientific classification) treatments (i.e. different names being applied), and for understanding of the geographical origins of commensal plants. Rorippa palustris is a cosmopolitan watercress found throughout tropical and temperate regions has 68 synonyms, and in Aotearoa has been known by at least 5 different botanical names (Garnock-Jones, 1978). By contrast, Rorippa divaricata was first described in 1988, prior to being R. gigantea (Hook.f.) Garn.-Jones in 1978 (Garnock-Jones, 1978; Garnock-Jones and Jonsell, 1988). These polymorphic traits also lead to frequent mis-identification as an exotic species from Europe (e.g. specimens of R. palustris from Aotearoa have often been identified as R. islandica (Garnock-Jones, 1978)). The life history of R. divaricata can change, from perennial to annual, depending on local growing conditions. It can grow up to 1-2m in height but can also grow low to the ground (Webb et al. 1988; http://www.nzpcn.org.nz).

Although Banks and Solander collected a number of cress species and numerous specimens in 1769, it wasn’t until 1834 that Richard Cunningham, whilst collecting Rorippa divaricata, in the Bay of Islands (K000693372, then described as R. stylosa), that he recorded the te reo Māori name matangoa from an informant. It is uncertain if other ingoa Māori have been applied to this plant in other parts of Aotearoa. General names for watercress including kōwhitiwhiti and poniu (more frequently applied to R. palustris) have been given to the introduced watercress Nasturtium officinale that may have also been applied to R. divaricata by some Māori in the past.

By the end of the 19th century, Thomas Kirk observed that R. divaricata was not uncommon in the Auckland region, but had a restricted distribution elsewhere (Kirk, 1899). It was recorded on the Kermadecs (Raoul) by Thomas Cheeseman in the late 19th century (Cheeseman, 1887), but it has not been observed there since (Sykes et al., 2000). It is still located on the Manawatāwhi, Tawhiti Rahi (Poor Knights) and across many offshore islands in the Hauraki Gulf (http://www.nzpcn.org.nz). It has only been located during recent collections from restricted locations throughout the North Island and the northern South Island (http://www.nzpcn.org.nz). It has also been observed as a seral plant occupying freshly disturbed soil or landslips, being more often located on lake and river margins. Plants have also been observed growing around the burrows of petrel colonies on the offshore islands of the Hauraki Gulf. It is currently restricted in distribution to two mainland North Island sites and one mainland South Island site, and is otherwise known from five off-shore islands, but all populations are very small (800-1000 plants in total). For this reason it has been regarded as Critically Endangered (Lange et al., 2004).

Matangoa is regarded as an endemic to Aotearoa, but has a close morphological affinity to the Australian species R. gigantea, as it has formerly been described (Garnock-Jones, 1978). By contrast, it has been long debated whether R. palustris is indigenous to Aotearoa, or was introduced by Polynesians (Webb et al., 1988). Common throughout the Northern Hemisphere, the distribution of R. palustris across the Southern Hemisphere is less certain. It does not grow on any of the tropical Pacific Islands, which suggests that it may not have been introduced to Aotearoa by Polynesians. Allan Cunningham recorded Nasturtium sylvestre, in the 1830s from Norfolk, which may have been mistaken for R. palustris. However, this cress has not been recorded since, and no specimens have been found in herbarium collections (Green, 1994). If R. palustris was found on Norfolk, it then is conceivable that this plant may have been collected from the island during the brief Polynesian settlement between 1220-1410 years cal. AD (Anderson and White, 2001), then transported to Aotearoa.

Figure 3. (left) Stems, leaves and fruits of a specimen of matangoa Rorippa divaricata collected by Banks and Solander in 1769, location uncertain. Image source: http://www.collections.tepapa.govt.nz.

(bottom right) Micrograph of fossil R. rorippa seed (whole) from Tamewhera, Ahuahu radiocarbon dated to ~1500 AD; 1.2 mm diameter

Pūhā (sow thistle)

Banks regarded the sow thistle he observed at Te Whanganui-o-Hei as ‘wild’ (Banks, 1962, p. 19), despite having collected it previously from Anaura Bay on the 8th October 1769 (See Figure 4). This likely reflected his poor understanding of Māori cultivation practices, or at least of fallow vegetation. Leach (1997:147) points out that ‘an agricultural mindset [in the absence of stock animals] prevented the majority of European observers from recognizing the achievements of traditional Maori horticulture’. Solander, by contrast, in his unpublished summary of the New Zealand flora Primitiae Florae Novae Zelandiae, regarded the sow-thistle as a cultivated plant ‘in graminosis et cultis’ (Hatch, 1963). Robert Anderson on the HMS Resolution voyage of 1772 to Queen Charlotte Sound (northern South Island) noted the presence of ‘sow-thistles’, but no mention was made to its cultivation status. Also on the Resolution was Georg Forster who later recorded that S. oleraceus L. [probably synonymous with S. kirkii) was:

‘Reperitur in Novae Zeelandiae et in amicorum insulis, satis frequens. Ejus caules tenelli et folia juniora pro acetariis a nostratibus usurpari solebant’ [trans. Found in New Zealand and Tonga, quite frequent. Tender shoots and young leaves are used for salad, as we had consumed it] (Forster, 1786, p. 71).

Pūhā raurōroa S. kirkii is regarded by some as tougher to chew and more bitter to taste than S. oleraceus (https://maoriplantuse.landcareresearch.co.nz), but this may result from the currently restricted ‘wild’ growing conditions and different soil substrates from Māori cultivations.

The high morphological similarity between three species of sow-thistle, including S. oleraceus and S. asper, both presumed to be exotic to Aotearoa and the Pacific Islands, and S. kirkii, an endemic, makes it difficult to conclusively determine what plants were observed in 1769. From the herbarium collections taken by Banks and Solander, different plant taxonomists have designated different names for these Sonchus specimens, but most recently P.J. Garnock-Jones designated them all as S. kirkii. Unfortunately, there is a lack of early collections of Sonchus from the Pacific Islands preventing any firm conclusions on the origin of S. oleraceus or S. asper, regarded by some botanists as exotic (Prebble, 2008) or indigenous (Whistler, 2009).

Later observations of sow thistles reveal that S. oleraceus quickly spread across Aotearoa after initially becoming naturalised in 1832 (Webb et al., 1988). In the 1840s, after spending a decade between Waimate in Ipipiri, and later Whanganui, Rev. Richard Taylor found that ‘the sowthistle springs up spontaneously in every spot which has been cultivated, and is generally used as a vegetable by the natives’ (Taylor, 1848). Thomas Kirk noticed that by the late 19th century, S. kirkii was restricted to coastal cliff habitat from Ipipiri to Rakiura/Stewart Island, but ‘rarely occuring in great abundance’ (Kirk, 1893). He also noted that: ‘I have never seen this form on cultivated land, and, as far as I am aware, it is absolutely restricted to maritime localities’. From ongoing surveys, S. kirkii has now regarded as being at risk of extinction, with this decline likely following the naturalisation of S. oleraceus and the expansion of pastoral farming practices (http://www.nzpcn.org.nz). The status of S. kirkii in Aotearoa highlights the possibility that other species of pūhā may have been prevalent across the Pacific Islands prior to European arrival, which has been suggested for Rapa Nui (Flenley et al., 1991; Horrocks et al., 2017).

Figure 3. (left) Stems, leaves and fruits of a specimen of matangoa Rorippa divaricata collected by Banks and Solander in 1769, location uncertain. Image source: http://www.collections.tepapa.govt.nz.

(bottom right) Micrograph of fossil R. rorippa seed (whole) from Tamewhera, Ahuahu radiocarbon dated to ~1500 AD; 1.2 mm diameter

Aside from the fossil data, described below, botanical surveys and ethnographic observations from the 19th century of Alan Cunningham, John Bidwill, William Colenso, Alan Travers, Joseph D. Hooker, Thomas Kirk and Thomas F. Cheeseman and others, identified that all of these korare were once widespread across northern Aotearoa, and most likely associated with taro or kumara cultivations, but are now restricted to the offshore islands, or coastal cliffs or other inaccessible coastal localities (https://www.nzpcn.org.nz/).

Table 1. Status of celery (Apiaceae) in Aotearoa prior to European contact

Botanical species collected in Aotearoa by Banks and Solander in 1769; herbarium accessions; # of synonyms | Archaeobotanical & palaeobotanical records from Aotearoa | Archaeobotanical & palaeobotanical records from elsewhere in Polynesia |

Apium prostratum subsp. prostratum var. filiforme (A.Rich.) Kirk; AK 189279, WELT 63736; 5 | Apiaceae and Apium pollen recorded from numerous sites1 | Apiaceae pollen recorded from numerous sites |

Centella complex including C. asiatica (L.) and C. uniflora (Colenso) Nannf.; WELT 63733; 28 | Rarely identified in fossil pollen records1 | Introduced to much of Polynesia (Whistler, 2009) |

Hydrocotyle heteromeria A.Rich.; AK 104432, WELT 63735; 1 | Apiaceae and Hydrocotyle pollen recorded from numerous sites1; Hydrocotyle aDNA recovered from both sediments | None |

Hydrocotyle moschata G.Forst.; WELT 63732; 4 | Hydrocotyle moschata type pollen recorded1; Moturua (achenes) | None |

Hydrocotyle novae-zeelandiae; WELT 63734; 4 | Apiaceae and Hydrocotyle pollen recorded from numerous sites1; Ahuahu (achenes)2, Moturua (achenes) | None |

Scandia rosifolia (Hook.) J.W.Dawson; AK 189114, WELT 63739; 3 | Apiaceae pollen recorded from numerous sites; no specific records of this species | None (genus endemic to Aotearoa) |

1(Moar et al., 2011),2(Prebble et al., 2019)

Table 2. Status of scurvy grass (Brassicaceae) in Aotearoa (Lange and Norton, 1996)

Botanical species collected in Aotearoa by Banks and Solander in 1769; 1769 herbarium accessions; # of synonyms | Archaeobotanical & palaeobotanical records from Aotearoa | Archaeobotanical & palaeobotanical records from elsewhere in Polynesia |

SCURVY GRASS Cardamine corymbosa Hooker, C. dolichostyla Heenan, or C. forsteri Govaerts; AK 100053-100054, 184766, CHR 450696, WELT 6395 |

Brassicaceae pollen recorded in numerous fossil pollen sites; Ahuahu (seeds) ; Cardamine aDNA recovered from sediments |

None |

Rorippa divaricata (Hook.f.) Garn.-Jones & Jonsell; WELT 63694 (a, b), 78887; 6 | Brassicaceae pollen recorded in numerous fossil sites; aDNA of Rorippa recovered from both sediments and coprolites; Ahuahu (seeds); Moturua (seeds). | Brassicaceae type pollen recorded in numerous fossil sites. Seeds of Rorippa sarmentosa recorded on Rapa |

Rorippa palustris (L.) Besser; AK 100057-100058; WELT 63693(a,b); 60 | Brassicaceae type pollen recorded in numerous fossil pollen sites; Ahuahu (seeds); Moturua (seeds). Rorippa aDNA recovered from both sediments and coprolites | Norfolk Island? Allan Cunningham recorded Nasturtium sylvestre, in the 1830s. It has not been recorded since, and no specimens have been found in herbarium collections (Green, 1994). Brassicaceae pollen has been identified from a fossil site from Norfolk (Macphail et al., 2001) |

Lepidium flexicaule WELT 63696(a,b); 1 | Lepidium pollen recorded in some fossil sites | Not present |

Lepidium oleraceum Sparrm.; WELT 63697; 2 | Lepidium pollen recorded in some fossil sites | Brassicaceae pollen recorded in some fossil sites ; seeds of L. bidentatum recorded from Rapa |

Table 3. Status of pūhā/sow thistle Sonchus species (Asteraceae) in Aotearoa

Botanical species observed in the Society Islands & Aotearoa by Banks and Solander in 1769; 1769 herbarium accessions; distribution; # of synonyms | Archaeobotanical & palaeobotanical records from Aotearoa | Archaeobotanical & palaeobotanical records from elsewhere in Polynesia |

Sonchus spp. (Asteraceae); probably S. aspera observed in the Society Islands; S. kirkii Hamlin, an endemic; WELT 63837; observed in North Island and Marlborough Sounds, and many offshore islands; 2 | Lactuceae type pollen recorded in numerous fossil pollen sites; Ahuahu (S. kirkii achenes); Moturua (S. kirkii achenes); Kohika swamp pā (S. aspera or S. kirkii achenes) | Sonchus pollen has been recorded on Rimatara, Tubuai, Raivavae, Rapa (French Polynesia). It is possible that variants of S. aspera or S. kirkii were indigenous to some Pacific Islands, but are now extinct. |

Additional References

Allan, H.H., 1961. Flora of New Zealand, Volume I. Government Printer, Wellington.

Anderson, A., White, P., 2001. The Prehistoric Archaeology of Norfolk Island, Southwest Pacific. Rec. Aust. Mus. 27, 1–142. https://doi.org/10.3853/j.0812-7387.27.2001.1334

Banks, J., 1962. The Endeavour Journal of Joseph Banks 1768-1771 Volume 2. Angus and Robertson, Sydney.

Beaglehole, J.C. (Ed.), 1976. The journals of captain James Cook on his voyages of discovery: Volume III part 1: The voyage of the resolution and discovery 1776-1780, in: The Journals of Captain James Cook on His Voyages of Discovery: Volume III Part 1: The Voyage of the Resolution and Discovery, 1776-1780.

Burkhill, I.H., 1935. A dictionary of the economic products of the Malay Peninsula. Ministry of Agriculture and Co-operative, Kuala Lumpur.

Cheeseman, T.F., 1887. On the flora of the Kermadec Islands; with notes on the fauna. Trans. Proc. New Zealand Inst. 20, 151–181.

Colenso, W., 1869. On the geographic and economic botany of the North Island of New Zealand. Transactions of the New Zealand Institute 1, 1–58.

Cook, J., Beaglehole, J.C., 1968. The voyage of the Endeavour, 1768-1771, Volume I. Published for the Hakluyt Society at the University Press, Cambridge [England.

Dunmore, J., 1981. The Expedition of the St. Jean-Baptiste to the Pacific, 1769-1770: From Journals of Jean de Surville and Guillaume Labé. Hakluyt Society.

Flenley, J.R., King, S.M., Jackson, J., Chew, C., 1991. The Late Quaternary vegetational and climatic history of Easter Island. J. Quat. Sci. 6, 85–115. https://doi.org/10.1002/jqs.3390060202

Forster, G., 1786. De plantis esculentis insularum oceani australis. Haude and Spener, Berlin.

Garnock-Jones, P.J., 1978. Rorippa (Cruciferae, Arabideae) in New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Botany 16, 119–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/0028825X.1978.10429664

Garnock-Jones, P.J., Jonsell, B., 1988. Rorippa divaricata (Brassicaceae): A new combination. New Zealand Journal of Botany 26, 479–480. https://doi.org/10.1080/0028825X.1988.10410652

Green, P.S., 1994. Flora of Australia. Australian Government Pub. Service.

Hatch, E.D., 1963. Solander — His influence on New Zealand botany. Tuatara 66–71.

Horrocks, M., Baisden, T., Flenley, J., Feek, D., Love, C., Haoa-Cardinali, S., Nualart, L.G., Gorman, T.E., 2017. Pollen, phytolith and starch analyses of dryland soils from Easter Island (Rapa Nui) show widespread vegetation clearance and Polynesian-introduced crops. Palynology 41, 339–350. https://doi.org/10.1080/01916122.2016.1204566

Kirk, T., 1899. The students’ flora of New Zealand and the outlying islands. John Mackay, govt. printer, Wellington, N. Z.,.

Kirk, T., 1893. Remarks on the New Zealand sow-thistles, with description of a new Species. Trans. Proc. New Zealand Inst. 26, 263–266.

Kodicek, E.H., Young, F.G., Hartley, H.B., Jones, R.V., 1969. Captain Cook and scurvy. Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London 24, 43–63. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsnr.1969.0006

Lange, P.J. de, Norton, D.A., Heenan, P.B., Courtney, S.P., Molloy, B.P.J., Ogle, C.C., Rance, B.D., Johnson, P.N., Hitchmough, R., 2004. Threatened and uncommon plants of New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Botany 42, 45–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/0028825X.2004.9512890

Lange, P.J.D., Norton, D.A., 1996. To what New Zealand plant does the vernacular “scurvy grass” refer? New Zealand Journal of Botany 34, 417–420. https://doi.org/10.1080/0028825X.1996.10410705

Leach, H., 2005. Gardens without weeds? Pre-European Maori gardens and inadvertent introductions. New Zealand Journal of Botany 43, 271–284.

Macphail, M., Hope, G., Anderson, A., 2001. Polynesian Plant Introductions in the southwest Pacific: Initial Pollen Evidence for Norfolk Island. Records of the Australian Museum 27, 123–134.

Moar, N.T., Wilmshurst, J.M., McGlone, M.S., 2011. Standardizing names applied to pollen and spores in New Zealand Quaternary palynology. New Zealand Journal of Botany 49, 201–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/0028825X.2010.526617

Prebble, M., 2008. No fruit on that beautiful shore: What plants were introduced to the subtropical Polynesian islands prior to European contact?, in: Clark, G., Leach, F., O’Connor, S. (Eds.), Islands of Inquiry: Colonisation, Seafaring and the Archaeology of Maritime Landscapes. ANU Press, Canberra, pp. 227–251. https://doi.org/10.22459/TA29.06.2008.15

Prebble, M., Anderson, A.J., Augustinus, P., Emmitt, J., Fallon, S.J., Furey, L.L., Holdaway, S.J., Jorgensen, A., Ladefoged, T.N., Matthews, P.J., Meyer, J.-Y., Phillipps, R., Wallace, R., Porch, N., 2019. Early tropical crop production in marginal subtropical and temperate Polynesia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 201821732. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1821732116

Salmond, A., 1991. Two Worlds: First Meetings Between Maori and Europeans, 1642-1772. University of Hawaii Press.

Sykes, W.R., West, C.J., Beever, J.E., Fife, A.J., 2000. Kermadec Islands flora – special edition: a compilation of modern material about the flora of the Kermadec Islands. Kermadec Islands flora – special edition: a compilation of modern material about the flora of the Kermadec Islands.

Taylor, R., 1848. A leaf from the natural history of New Zealand; or, a vocabulary of its different productions &c.,&c., with their native names. R. Stokes; J. Williamson, Wellington; Auckland.

Webb, C.J., Sykes, W.R., Garnock-Jones, P.J., 1988. Flora of New Zealand, Volume IV. Botany Division, DSIR, Christchurch.

Whistler, W.A., 2009. Plants of the canoe people: An ethnobotanical voyage through Polynesia. National Tropical Botanical Garden, Kalaheo.