Jack Thatcher

Becoming the Light:

On the historical, technological, cultural continuity of Pacific voyaging

Becoming the Light: On the Historical, Technological, Cultural Continuity of Pacific Voyaging

Jack Thatcher CNZM joined Te Aurere whanau more than 40 years ago, and has logged more than 35,000 nautical miles of waka voyaging. He is of Ngai-te-Rangi, Ngati Ranginui, Ngati Porou and Te Aitanga a Hauiti descent. Thatcher is one of those few initiated by Pius “Mau” Piailug, the traditional master navigator. Chairman and co-founder of Te Puna I Rangiriri Trust (TPIRT) he has organized instruction for hundreds of young people in traditional Māori knowledge, particularly regarding waka and navigation. For the 150-year commemoration of Te Tiriti o Waitangi Thatcher navigated the Mātaatua Waka, captained the Waka Odyssey voyage for the 2018 New Zealand Festival of the Arts, served as flotilla kaitiaki for Tuia 250 commemorations, and was chief navigator for Sir Heke Busby’s Waka Tapu project.

After the Voyaging Wananga, Arakite Trustees determined that a deeper explanation of the transmission of the arts of traditional navigation would balance the conference – such knowledge is core to its purpose – and add to readers’ understanding. The Trustees sent Proceedings editor Bill Guthrie to learn more of Jack Thatcher’s way. The following is Guthrie’s paraphrase of the audio recording of that interview.

The Pacific navigator who performed initiation for the traditional navigators who now teach the art was Pius “Mau” Piailug. Mau traced his ancestry back 3000 years, to the first navigator in his world. Of course, it is easier for him, than for me, because he lives on the island where that ancestor lived. Mau was five years old when he began his training. Mau initiated me as a navigator when I was thirty, and my ancestors in New Zealand don’t go back 1000 years. And yet, I am a direct inheritor, now knowing, if before unknowing, of that voyaging tradition. Navigators like Mau carried my people here, to this place, and carried our people, mine and Mau’s people, from Southeast Asia, across 5000 thousand miles of the ocean most of you call the Pacific.

Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa is what we Māori called the waters around us. I am Māori. I am also a Kiwi, named for my grandfather, who died at the Somme, and his father, who had the same name. I began navigating with the Army, as a cadet. So my first grasp of navigation is very mathematical, and schematic. My mind is trained by these experiences so it follows a single track. Not tunnelled, at all, because in the Army and in waka navigation, the mind must be open, and eyes, too. But I am always thinking about the work and the responsibility in my hands at that moment. So I am a modern Kiwi. But I am also the trained, initiated recipient of the thousands of years of Pacific navigators’ tradition.

Mau Piailug was born in Yap, as were his ancestors for the last few thousand years. According to the people who call the ocean “Pacific” that makes him Micronesian, while I am, according to the same people, Polynesian. Mau answered a journalist who asked about that, “Hey, what’s a Polynesian? What’s a Micronesian? It’s not us that draws the lines?” He is right, regarding voyaging. The Pacific is cut up, categorized. By other people. Not by the people who live here. In our world, regarding voyaging, is only one thing: Pacific voyaging, before the Europeans, represented one technology. Look around the Pacific. From the Philippines to Aotearoa, to Rapa Nui, to Hawaii, and back to Taiwan – which draws the edges of a diamond-shaped map of known Polynesian voyaging, 20,000 miles around, an area of about 20 million square miles – and there are double-hulled canoes sailing between islands. Nothing else. Now, a thousand years ago European ocean voyaging could be drawn in a triangle with corners at Norway, Labrador and North Africa, which boundary measures 8000 miles, covering an area of about 3 million square miles, just to compare technology. We won’t discuss legends of one-way trips, and we will simplify that exclusion by the Ed Hillary Rule: Only both ways counts. Up and down, out and back. Or it is not exploration. It is not discovery. The maps I have described here are the voyaging maps everyone knows and everyone accepts, so far as going and returning, which is voyaging.

Voyaging whether of the Pacific or of the Atlantic, is one technology, with two streams. One stream is creating the technology, in the sense of making the tools. The other is gathering the knowledge around those tools.

There is an idea out there, not among us navigators, that the Polynesians started voyaging perhaps from the Santa Cruz Islands, at the eastern edge of the Solomons, and by 3500 years ago had only made it to Fiji, which itself is the eastern outpost of the Polynesian hub of Tonga, Samoa and Fiji. And then, this outsiders’ story goes, we forgot how to voyage. What passes for evidence of our forgetfulness is that we did not reach the Marquesas until 2500 years ago. By the way, that is almost 3000 miles from Fiji. Putting aside, for the moment, our traditions, our knowledge, the knowledge of the people who live on and around this world of water, it should be noted that the trip from Fiji to the Marquesas is 3000 miles. Making our way from New Guinea to Fiji would have been done by legs amounting to island hopping, of a few hundred miles a trip. Between Samoa and the Marquesas, there is very little land, few islands, and small. I do not think any voyager, any navigator, thinks we forgot how to voyage.

Consider the problem this way: One voyaging system made up of two streams of technology, learning to make the tools, and then making the knowledge to use the tools. We do this even now, we who build and sail our own boats. Or even if you were young and your family let you use a dinghy, and you rowed it, and then put up a sail. Well, how long is it between the time you have a sail, and you sail it to an island you can see offshore? Societies learn, about like people learn.

The people of the Pacific had the single dugout canoe tens of thousands of years ago. Perhaps they added a sail after twenty thousand years? An outrigger would have made it stable, and you could land bigger fish. The outrigger would have begged for a sail, if not raised beforehand. Then a little deck, and what all can be done with that? Now two hulls. A big sail. Full decking. A hut. Fire pit! At this point, remember that Northern European ships did not accomplish this level of technological innovation in form in its whole pre-modern history. They added equipment to the single hollow hull, and increased its size, but never developed really different layouts of ships. We had the dugout, the planked monohull, the outrigger, the double outrigger and the double-hull waka hourua.

You see, then, that the development of the boat for voyaging is one thing. Learning to use it is related, but it is something else. There are many more steps between on one side having the tool – the boat – and the knowledge – the navigator – on the other, and the voyage. Many steps.

My first voyage as navigator I guided the waka from New Zealand to Hawaii. Maybe I knew one twentieth of what Mau knew. But that five percent was enough to teach me to navigate by stars and sun from the South Pacific to the North Pacific, across the equator, and to come up right on the shore of Hawaii, not to the east or west.

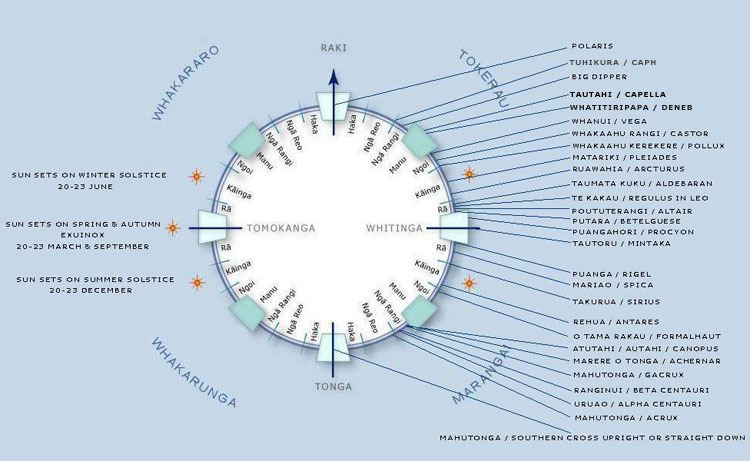

When I did that first navigation I had 49 stars to memorize. Stars to help me throughout my voyage. I had to memorize where the sun was, for the whole voyage. I was taught, and I remembered, how the sky was divided up. From those clues and signs and that plot of the heavens, I had directions I needed for the whole voyage. And my first voyage as navigator was to Hawaii. All I did was to execute my training, to do as I had been taught. I relied on the wisdom of the ancestors, as Mau Piailug relied on the ancestors.

One other thing Mau taught me, one blessing of the ancient initiation. I was given The Light. Really, Mau said I was made The Light. Enlightenment is the word in English. In Mau’s language, it is The Light. I must be the light to my waka, to my crew, and to my students. Not only must I share this light, this knowledge, this light means one more thing. First, in everything, I am responsible for preserving life. I think other traditions of way-finding – every nation has a way of marking roads, written or unwritten – they teach navigation is first about the technology of knowledge. Pacific traditional navigation teaches the first principle is life. The navigator’s first responsibility is preserving life. This is the light passed from the tupuna to us, the navigators.

Now, think about the unity of this tradition. Micronesian, Melanesian, Polynesian – whatever outsiders want to call us – anyone who voyaged in the Pacific used outriggered and multihulled vessels, sailed to the stars and the sun, not to paper targets, and observed the waves and winds, the same waves and the same winds, and took cues from birds, fish, whales and seaweed. Regardless of different blood or different languages, the sea and the sky were same. And the technology was shared.

My initiation in Yap shared not just the sailing technology, but the spirits of voyaging. I follow my mother’s Catholic religion – which is Western, as is my original mathematical bent in land navigation – and yet I see the use, the need, the place of the elemental spirits, the relation with elements themselves, and the names the Pacific tupuna have given them. Wind, lightning, all weather is Tāwhirimātea. The sea is Kiwa, or Tangaroa. Sky is Ranginui. The Melanesians have different words, though the prayers and chants of the Yap people taught me that our Māori karakia honoring these elements are things we did not invent when we found Aotearoa. They were chants the voyagers brought here. The karakia for the weather keep us alive on the water. Though they are preserved in somewhat landlocked modern Māori memory, they matter less to the gardener than to the sailor. My students here learn their karakia in Te Reo. Only a little while ago, the waves rose up against the wind. Two elemental spirits contending over us. We thought a great storm would come. We sang our karakia, and it seemed to all of us that the waves were smoothed and the wind blew more around us instead of on us.

Such escapes are partly faith, partly learning and knowledge, and partly technology. All these things are inherited, and it proves to us the integrity of the voyaging tradition. Even though our grandparents and great-grandparents did not have our Māori voyaging knowledge, their tupuna knew, and that knowledge is why and how we Māori are here, now.

The initiation, and the detail of its knowledge, and how many start such schools though few graduate, these all demonstrate something else about our ancient origins. Now I think no serious academic believes our discoveries were accidents, and they have their own reasons for that: archaeology, genetics, the kumara, some even think the chicken. But we have our own knowledge to prove to us that our tupuna knew the final lesson: how to go, and how to return, and how to go again, and return again. And so they explored the seas and found the lands. This knowledge also proves, to us, that few ships of exploration were lost.

The Polynesian population was never large. The initiates, the tohunga, the colleagues of Tupaia were never numerous. If the Pacific peoples launched many failed expeditions, the cadre of navigators would have been cut down. Then no one could have led the fleets of settlers. Our legend speaks of fleets. Modern genetic studies begin to support what our knowledge already recorded. In the face of that evidence, did any large number of explorers disappear? Well, that is a puzzle piece that does not fit. I believe the success of the voyages, the movement of large numbers of settlers, the movement and exchange of food plants and animals, all these show that traditional Pacific voyaging technology worked. I think no one really doubts that the technology worked, but my argument goes one step further: The knowledge worked. The knowledge was teachable, reliable, and it got us there, and back, and there again, and back, again. And the knowledge, the light, represented by the navigators, preserved both life and itself, the knowledge.

On my first voyage as navigator, we came to the equator in the dark. Big moon. We crawled along at two knots, and dolphins came around us. Dolphins stayed with us two hours. Small ones, big ones, not just one pod of dolphins, or one kind. Many. We could not keep track of them. Under the big moon, the dolphins were followed by phosphorescent trails: circles, leaps, dives, criss-cross, under the waka, in front and behind. Huge moon above and phosphorescence all around us. From the first I knew the ancestors had come with us. Dolphins stayed with us across the equator and then they left.

When I got to Hawaii I talked to Pius Piailug, who was waiting there for us.

“Mau,” I said, “when you get to the equator, do you always get the dolphins?”

“Yes!,” Mau laughed.

I could not believe it, “Do you always?”

“Yes! They’re your ancestors.”

Star COMPASS

The modern-day star compass (kāpehu whetū) was developed by Polynesian navigator Nainoa Thompson and is based on the Micronesian star compass that grandmaster navigator Mau Piailug originally designed and used. Jack Thatcher made it useful for navigators from Aotearoa by translating it into te reo Māori. (Te Aurere/ Pokapū Akoranga Pūtaiao)

Waka art credit:

1300 Dawn – Krystal Woolfe