Dr. Wan Salleh Wan Ibrahim

Saturday 24.08.19 Session 2 Dr Wan Ibrahims presentation as presented by Dr Madam Tin Cho Ma ” The Malay-Polynesian Connections “

The Malay-Polynesians and its Diaspora Connections

Dr. Wan Salleh Wan Ibrahim THE WORLD MELAYU-POLYNESIA ORGANISATION Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Dr. Wan Salleh Wan Ibrahim is president of the World Melayu-Polynesia Organisation, and head of the Centre for Malay Heritage Arts from 2006 to 2012. Unable to attend the Wananga, his paper was read by Dr Madame Tin Cho Ma.

Our present world is very much into globalisation, easy travel and fast-track developments. We are also in the digital age where human relationships become minimal and less meaningful. However, we Malay-Polynesians, inspite of all these, need an ever concerted effort to interact, come together to boost cooperation in all areas.

We are increasingly challenged to sustain the values we uphold. The history and civilisation we had shared and built together must be maintained, for the sake of our new generation, and the generations that will follow. Despite this world becoming multicultural, giving little importance to indigeneity and cultural identities, the importance of exploring and reconstructing our roots, our DNA connections, own historical narrative of our peoples, our lands and our seas is always challenging. The organising of the present Voyaging Wananga in historical Waitangi is therefore a giant leap at rediscovering ourselves, our DNA connections, our kinship, and how capable we had been in our distant past. Our capabilities, our values and our stories need to be systematically recorded, transmitted for the new generation to be nourished in perpetuity.

Since the earliest of times, we Malay-Polynesians, from 14,000 – 12,000 BC, were the leading indigenous inhabitants of the earth spreading over the globe. We were leading explorers, settlers, agriculturalists, scientists and navigators of the world and second to none in these exploits. Between ourselves, we spread across about four-fifths of the globe, speaking more than 1200 variations of that root language. Despite the coming of others into our shores and our lands, the values we share are as ever shining as the morning sun.

Many of the present generation of scholars and historians in Asia had argued that the major and earliest civilisations of the world had been the Indian and Chinese. The standard world history sometimes omitted us from its mainstream reference. However, lately, honest Western prehistorians, marine archaeologists, linguists and anthropologists had discovered that Nusantara was once the centre of world civilisation, and that other civilisations, like the Sumeria, Mohenjo-Daro and Chinese Civilisation were passive recievers of the civilizational ingredients of Sunda Civilisation. We had lost ground in rediscovering and reconstructing our civilizational heritage the moment we were colonised by foreign powers during the 15th-17th century.

- CONCEPT OF MALAY-POLYNESIAN HISTORY

One prehistorian, Renfrew (2007) believe that pre-colonial Southeast Asia was not known until 1500 AD. The emergence of our countries from the colonial yoke was recent, between 50-100 years. The moment we attained independence, all textbook materials were couched in their histories and us as native participants within their margins of reference. The 15th through the 17th centuries was the colonists Age of Discovery, their writing of us was skewed and narrow, that we were portrayed half naked, half-dressed and indolent, devoid of civility and civilisation. One Malay scholars Syed Hussein Alatas – in studying this post-colonial experience in Java, Sumatra and Philippines – wrote The Myth of the Lazy Native (1970)’ It was hot reading for many intellectuals.

The West had been keen to find the Spice Islands, besides gold and other precious materials These sent Sequeira, Drake, Cook, Tasman, Alfonso, Raffles and Light to our shores. These names are said to be those of heroes and discoverers of our native lands, although we had been here 50,000 years before them.

We need to unlock one of our prehistoric archive – that is the existence of Sunda Civilisation. The Sunda Civilisation, its knowledge, its influence and global maritime reach may open our sense of history, our voyages, our crafts and our discoveries into a meaningful pattern, making sense of our present lives, sufficient and complete.

Indonesia has been our point of discussion here.

One Greek philosopher, Plato had been writing in his dialogue, Timaeus and Critias, about a hypothetical civilisation called Atlantis. He named it as Aurea Chersonesus. This `Atlantis’ was not at one geographical point but spread its own constellation of centres’ influence, though tied commercially to one mother city. It was estimated to be 9,600 BC. The problem of Atlantis’ reality or fiction had divided scholars in the past. However, one Oxford medical scientist-anthropologist, Stephen Oppenheimer brought out a book called `Eden in the East’ (1998).

Oppenheimer was a medical scientist in Malaya, but undertook many studies into the Orang Asli (natives) and over time gathered oral and written evidence of this region. He studied flood effects of the Great Flood of Noah, its probable cause of volcanic eruptions and overall catastrophism in the Nusantara and Sunda Platform, especially. Then he concluded, with all these characteristics, Indonesia must be this Atlantis. The major city zone had been between the tip of Java and Sumatra guided in by the Sunda Strait to a cluster of islands called Krakatoa. It was the volcanic explosions of Krakatoa that sunk the Sunda Platform submerging the cities and population.

The present sea level was 150 metres above the past at the time of cities and civilisation.

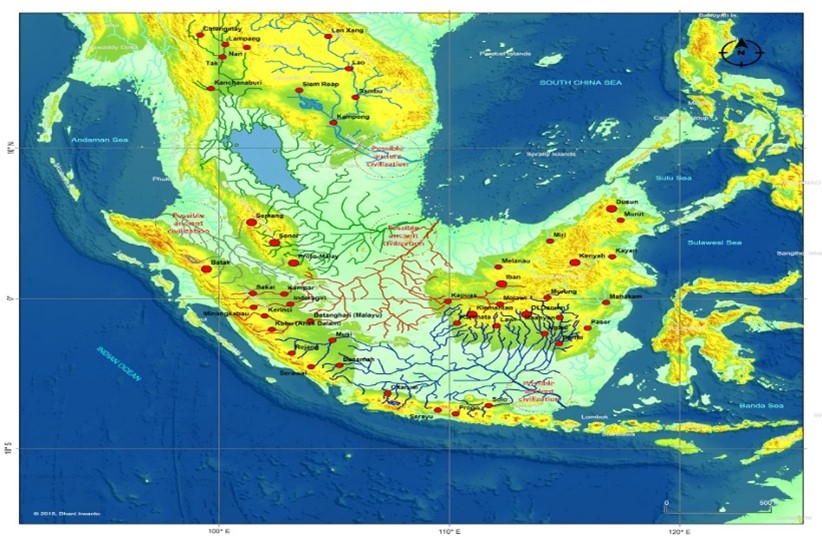

Sunda (Figure 2} is the geographical platform of well drained land and rivers around the Malay Peninsula and Sumatra -Java islands about 10,000-12,000 BC.

Source: https://www.bing.com/images/searchview

Figure 2: Sunda Platform with intersecting rivers

By description, inhabitants that once called Sunda people – Sundalanders – were great inventors of watercraft, enabling island hopping and ocean -going trade and discovery.

They also developed deep ocean-going technologies, like the catamaran, the outrigger ship, tanja sail and the crab claw sail. The Chinese historian, Wan Chen (220-200 BC), also mentioned these technological advances by the Javanese and Sumatrans.

In our Malay history, we even had one navigator by the name of Panglima Awang (Enrique the Black)(Figure 3), who accompanied the Spanish adventurer, Ferdinand Magellan in 1521, completed his journey round the world.

Source:3.bpblogspot.com

Figure 3: First Malay sailor/navigator to go round the world

All these developments intrigued us (Hj. Ahmad Zainudin, Nik Hassan Suhaimi and me) to collaborate in writing a conference paper entitled. `Sunda Civilisation’. It was presented in a conference themed `The Malay-Maori Affinity Conference’ (2002) organised by Massey University, North Shore, New Zealand.

There was little response as the subject was new to that audience. However, in the Indonesian and Filipino archaeological circles, there were fantastic responses followed by major conferences held in Indonesia and Philippines.

The Atlantis story in Indonesia was very compelling. Based on Oppenheimer’s study, there was a geological platform called Sunda. It was the first human civilisation, until it sank into the sea as result of three volcanic eruptions.

Yet again in 2011, another book `Atlantis the Lost Continent Finally Found’ (Figure 2) was written by one Brazilian scientist, Professor Arysio Santos.

Figure 4: The book by Santos

His theory was that Indonesia was this fictional Atlantis, arguing the local Sanskrit name Atala is the Greek term Atlantis. Santos elaborates that the nesos stands for islands (ibid:9).

There is another twist to this, in that my own understanding of the Greek term, `Makarion Nesos’, refers to a cluster of island civilisations, meaning nusantara. The term `nusa’ in Indonesian corresponds with the Greek term `nesos” while `antara’ signifies interconnectedness like a seamless chain of islands functioning like little land bridges.

Ironically, this meaning had escaped many historians in the Indo-Malayan world – until Oppenheimer’s and Santos’s revelation.

The credibility of the Sunda story ties very well with our theory of the early origin of Malay-Polynesians.

- Histories and early ethnologists

The cryptic `brown peoples’ of Asia; this is ethnography of great significance.

The earliest historian known in the western world was Herodotus (484-425 BC). He wrote tremendously on the Greeks, but had very little knowledge on brown Asians beyond Anatolia (Turkey) and countries beyond. The ancient Chinese of Asia – likewise – had described these as `brown Asians’, as `Kun Lun peoples’. The term `kun lun’ comes from the Kunlun Mountains, located at the northern edge of the Tibetan Plateau of the Tarim Basin. Many theories came about as to the origins of the Malays or Kunluns, being a population of Malai, proto-Nagas of the Assam, as their culture and linguistic having similarities with present day Malays of the Peninsula Malaya. Indeed, the term Himalaya was a term associated with the Malays too.

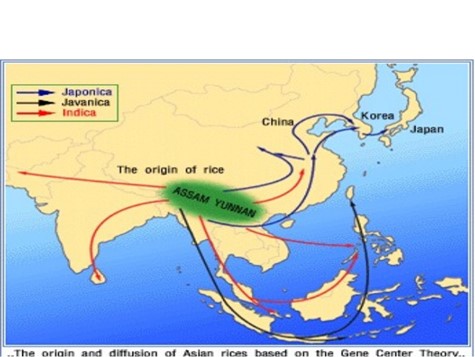

Rice agriculture was another cultural marker of the Malays (Figure 5).

Source:https://image.slideshareedn.com

Figure 5: Malay rice culture marker

Domesticated rice in the past began in the Assam-Yunnan. This fact brought in Heine-Gelderne’s theory that Malays as originating from Yunnan. It was a second wave migration while the first wave migration and diaspora was from Sunda.

The spread of rice was by the Austroasiatic Malays into central China (Wan Salleh Wan Ibrahim, 2011). This was about 1000 years before the Chinese overwhelmed them, causing migration into Taiwan.

The Taiwan theory introduced by Bellwood was not the full story, rather his account of Lapita Culture spread into the Philippines and Polynesia was half-truth.

The early Polynesian voyages took place in many parts of Polynesia. One likely place was from Rarotonga. The early seafarers were known to bring pigs, rats and kumara Besides kumara, rice is surprisingly a cultural marker for Polynesians of the Pacific as well. Hawaiki, the homeland, is termed by the Rarotongans (Buck, 1964: 21) as Atia te varinga nui.(Wan Salleh Wan Ibrahim, 2003) or `rice -origin Asia’. . In this article of mine, I traced an old history concerning Asia, in that it was of one nationality (Austro-asiatic) but had subsequently spread as `Austronesians’ as their diaspora voyages proceeded into greater Polynesia.

The first attempt to sort out this prehistoric ethnology came about through a German physician and anthropologist, Blumenbach. He wrote a book Unity of Mankind (1795) in which the races of humanity had been classified into five categories, namely white Caucasian, brown Malay/ Malaysian, black Ethiopian, Red American and white Mongolian. However, he was not racist though he had attempted a scientific race theory.

The Maoris had been classified as belonging to the Malay race (Bhopal, nzetc.victoria-acnz/tm/scolarly/tei-CraReco-t1-body-d36.html0) as their language, culture and physical characteristics testify them so.

Like the Malays, the Maoris place great significance to physical objects like land water and stone.

The cultural surveys of many Polynesian islands were done by Sir Percy Buck (1967). His ingenious command of languages of Polynesia stood out well to help understand their culture. `Hawaiki’ the homeland while `benua’ is the Malay term . The term `benua’ is `fonua’ (Tongan), `fanua’ (Samoan), `fenua’(Tahitian), `honua’ (Hawaian) and `phenua’ (Maori). As such the Maori consider themselves as tangata phenua (peoples of the upper north), meaning Asia.

Water is `air’ in Malay, `wai’ in Hawaiian and Maori; while `ikan’ (fish in Malay), `ika’ in Maori, `i’a’ in Hawaiian. Meanwhile `batu’ is stone in Malay, `patu’ in Maori, `patu’ in Taiwanese and `bato’ in Filipino Tagalog. Below (Figure 6) is the wide extent of the Malay-Polynesian language family’

Source: www.langauagesgulper.com/eng.Austronesian_files/dropped.image.jpg

Figure 6: Geographical spread of Austronesian language

2.3 Kotahi te iwi tatou (We are one people)

When we start identifying the Malay-Polynesian Ancestral Nations in 2012, we came to have 33 nations comprising 400 millions. The task of bringing them together for any unifying meet is ardous.

My interest in the Malay World was inspired by the late Prof. Dr. Ismail Hussein, who was at the forefront to promote love and consciousness of Malay literature and history. He was head of GAPENA (Association of Malay Writers), and through this association a series of conferences were held. Another historian and archaeologist is Prof. Dr Nik Hassan Shuhaimi, who has specialised in Malay history and origins.

3.0 THE NEED TO REWRITE HISTORY

Our shared historical and cultural heritage must not be forgotten. Such serious writing must be stressed and given attention at all times. History had been a waning subject in Malaysia lately, partly because few realised its importance in nation-building and wealth creation. However, Philippines and Indonesia had demonstrated to be highly historically conscious especially in asserting a new spirit of Malayness and geopolitical independence.

The Voyaging Wananaga that we have is a rare opportunity to start collaboration projects of mutual interest and benefit.

4.0 CONCLUSION

A brief introduction on Sunda Civilisation is attempted. Hopefully we are aware that we are all deeply integrated into one another and be able to build coalitions for productive work.

The task of writing our common history must not be left to others. We make our own destiny.

References

Asiapac Editorial (2013). Gateway to Malay Culture. Asia Pack Books, Singapore.

Barhhardt, A.O. Kawagley (2005). Indigenous knowledge systems and Alaska Native ways of knowing. Anthropology and Education Quarterly (36 (1), 8-23, 2005.

Blundell (2011).Taiwan Austronesian Language Heritage Connecting Pacific Island People:Diplomacy and Values, IJAPS, Vol. 7, No 1.

Bulbeck, D (2008). An Integrated Perspective On The Austronesian Daispora: The Switch from Cereal Agriculture to Maritime Foraging in the Colonisation of Island Southeast Asia, Journal of Australian Archaeology, Vol.67, Issue 1

Fraser, J. (1896). The Malayo-Polynesian Theory. The Journal of the Polynesian Society, Vol.V, p.100, June.

Hall, D.G.E. (1970). A History of Southeast Asia. New York: St. Martin Press

Hussein Othman (2005). Characteristics of Malay Historiography. SEASREP 10th Anniversary Conference, Southeast Asia, A Global Crossroad, Imperial Mae Ping Hotel, Chiang Mai, Thailand, 8-9 December.

Khin May Aung (2015). Historical Perspectives of Mon Settlements in Myanmar. International Working paper for Conference on Burma/Myanmar Studies: Burma/Myanmar in Transition: Connectivity, Changes and Challenges, Chiang Mai University, Thailand, 24-25 july

Leane R. Simpson(2004). Anticolonial strategies for the recovery and maintenance of indigenous system, American Indian Quarterly, 373-384.

Nik Hassan Shuhaimi Nik Abdul Rahman et al (2011). Alam Melayu Satu Pengenalan. Alam & Tamadun Melayu, UKM: Bangi

Nik Hassan Shuhaimi Nik Abdul Rahman (2013). Verifiable Memories of Historical Events in the Malay Classical Literary Sources. Asian Social Science, Vol.9, No. 6.

Renfrew (2007). Prehistory: Making of the Human Mind. Phoenix : London.

Santos. A. (2011). Atlantis The Lost Continent Finally Found. Atlantis Publications: Washington.

Shafer, L. N. (1996). Maritime Southeast Asia to 1500. M. Sharpe. Inc., New York.

Syed Hussein Alatas (1970) Myth of the Lazy Native. Frank Cass :London.

Wan Salleh Wan Ibrahim (2011). The Need for a True Symbiosis of Malay Culture and Its Built Environment. In MELAYU Jurnal Antarabangsa Dunia Melayu, Jilid 1, Bil. 1, Jun., pp. 127-145

Wan Salleh Wan Ibrahim (2012). Geneological Hierarchy of Malay Race in the World (in Malay). In Gagasan Melayu Serumpun. Shah Alam, Reka Cetak Sendirian Berhad, pp. 49-75.

——————————— (2013). Roots in Sanscritised Kambuja-desa: A Historical Reconstruction. Working Paper of Malay Heritage in Cambodia, Laos PDR and Vietnam 11, Royal Academy of Cambodia, 17 February.

——————————— (2013). Lifting the Curtains of Malay-Polynesian Prehistory Through Islamic Perspective. (In Malay). In Prosiding Kerajaan Melayu dan Hubungan dengan Kesultanan Brunei, Pusat Sejarah Brunei, Kementerian, Belia dan Sukan, Bandar Seri Begawan, Brunei, pp 88-105.

——————————- ( 2013a). Reconstruction of Indo-Malayan Archipelago’s Prehistory and the Eventual Peopling of Polynesia. Working Paper on Conference on Cultural Transfer in Historical Maritime Asia: Austronesia_Indo Encounters, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, University of Singapore, 2-3 December.

Internet Sources

`True History of Atlantis; (http://atlan.og)

A Commentary on the Relationship between Peninsular Malaysia and Yunnan During the Prehistoric Era {Spaj: ukm;my/jurnalarkeologi/indx.php/jurnal/arkeologi/artikcle/view:File/118/67

CUURICUL“ Johann Blumenbach and the Classification of Human Races” (https://www.encycloedia.com)